China-US trade talks cancelled: why negotiations will still happen eventually

Senior trade negotiators from the US and China had been due to have a virtual call on August 15 to check the progress of the “phase one” deal reached by the two nations in January, aimed at overcoming the trade war that has dragged on for the past several years. But it has since been announced that the talks have been postponed, with no new date set. The two sides cited scheduling conflicts and the need to allow China more time to make good on its commitments under the deal.

The high tensions between China and the US will presumably not have helped either. Donald Trump recently said he was not thinking about holding more talks, telling journalists: “We made a great trade deal. But as soon as the deal was done, the ink wasn’t even dry, and they hit us with the plague.”

So is there any chance of a breakthrough any time soon?

Progress so far

It seems a long time ago that the phase one deal was signed. It was always intended as a mini-deal to be followed by a second phase. The main commitment, effective from February, was a promise by China to purchase US$63.9 billion (£48.9 billion) more US goods and services in 2020 than in 2017. Further targets for 2021 require China to purchase an additional US$200 billion of goods and services over the two years.

The chart demonstrates how poor progress has been. Exports from China to the US have gone up in spite of COVID-19 (per the top dotted line), but the amount it is importing from the US (the bottom dotted line) has not picked up to the levels envisioned.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates that China imported less than 50% of what it should have done in the year to June. Barring a large upswing in the second half of the year, hitting the 2020 target looks unlikely.

Chinese trade with the US

US exports covered in the agreement include machinery, pharmaceuticals, aircraft, iron, steel, agricultural products, gas, oil and services. The deal was particularly important for US agriculture, whose barriers to trade have also been reduced through relaxing Chinese health and safety standards and other bureaucratic obstacles.

Meanwhile, the US pharmaceuticals sector was afforded additional protection through a commitment from Beijing to do more to enforce intellectual property rights against copycat manufacturers. However, other commitments such as access for financial-services providers were left vague and may be harder to enforce.

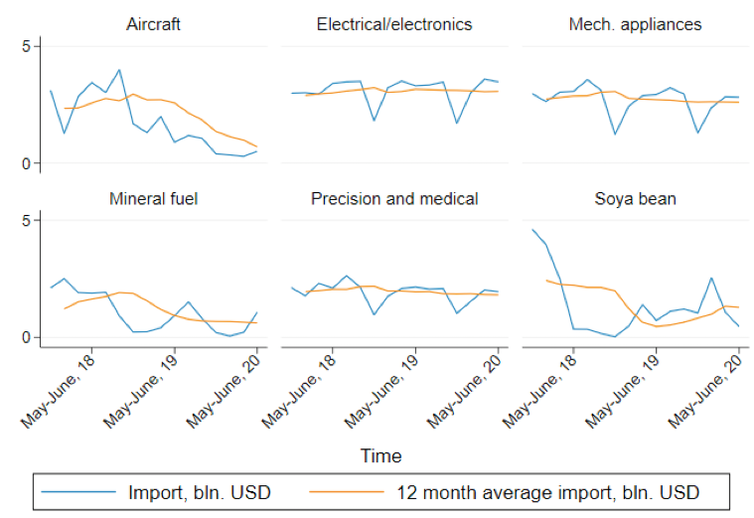

The next chart looks at some specific market segments. It shows a dramatic decline in Chinese imports of US aircraft and soya beans, while imports of mechanical appliances, electrical equipment and electronics are flat. The Peterson Institute’s data suggests that China had achieved around 24%, 27% and 5% of the end-of-year commitments in agriculture, manufacturing and energy respectively by June.

Chinese US imports by sector

China’s failure is not entirely surprising, given the collapse in global trade due to COVID-19. According to our calculations based on General Administration of Customs of China statistics, Chinese total exports to the rest of the world in May-June 2020 were only 1.2% lower compared to the same period of 2019, but their exports to the US were 6.9% lower. This may be because China has controlled the pandemic more successfully than the US.

Fresh impetus, perhaps through phase-two talks, is needed to get phase-one implementation back on track. Yet thanks to the wider disagreements that have engulfed the China-US relationship, talks looked unlikely even before the confirmation that the August 15 meeting had been postponed.

China-US tensions

From an American perspective, the upcoming elections are key. Polling suggests that both Republican and Democratic voters are increasingly negative about China, not least because of the pandemic. Trump’s tough stance is therefore politically savvy in an election year.

The Americans had expected to use phase two to negotiate over other trade concerns, such as Chinese tech. We have seen the US pressurising other countries such as the UK to follow suit on banning Huawei, while more recently Trump has turned up the heat on the likes of WeChat and TikTok.

There is also a plethora of divisive non-trade issues. Alex Azar, the US health secretary, visited Taiwan earlier in August. This was one of the highest-level US delegations in decades, and followed a recent Taiwanese delegation being hosted at the US state department. There are also increasing military tensions in the Taiwan Strait, and the US and China have been closing consolates in one another’s countries.

There is also the fallout from China imposing national security legislation on Hong Kong, prompting a US executive order that Hong Kong will be treated the same as mainland China for trade purposes. This means goods labelled “Made in Hong Kong” will no longer receive preferential treatment.

The US is Hong Kong’s second largest trading partner, and the territory will now endure the same tariffs imposed on Chinese goods. These are currently six times higher than before the trade war. The row over Hong Kong has also led to the US and China imposing sanctions on certain citizens from each other’s countries.

These tensions are very important, though many of them are longstanding. When the phase one agreement was signed, both the US and China were willing to put aside differences to improve trade. Tensions have undoubtedly escalated since then, but the tide may yet turn in favour of negotiations to implement phase one and explore phase two.

There are important matters to discuss in phase two, including bringing tariffs down to pre-trade-war levels. The US retained the restrictions as leverage last time around. There is also the question of imports after 2021, and China’s subsidies to state-owned enterprises. And with cyber-security a high priority for the US, the actions against WeChat and TikTok could be part of the negotiating strategy.

There are therefore numerous incentives to resume negotiations, even if they may not happen immediately. Ultimately, new negotiations will heavily depend on the result of the US elections and the post-COVID-19 economic recovery of both countries.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.