China destroys domes of famous mosques as cultural whitewash continues

China’s campaign to suppress Islam is accelerating as authorities remove Arab-style onion domes and decorative elements from mosques across the country.

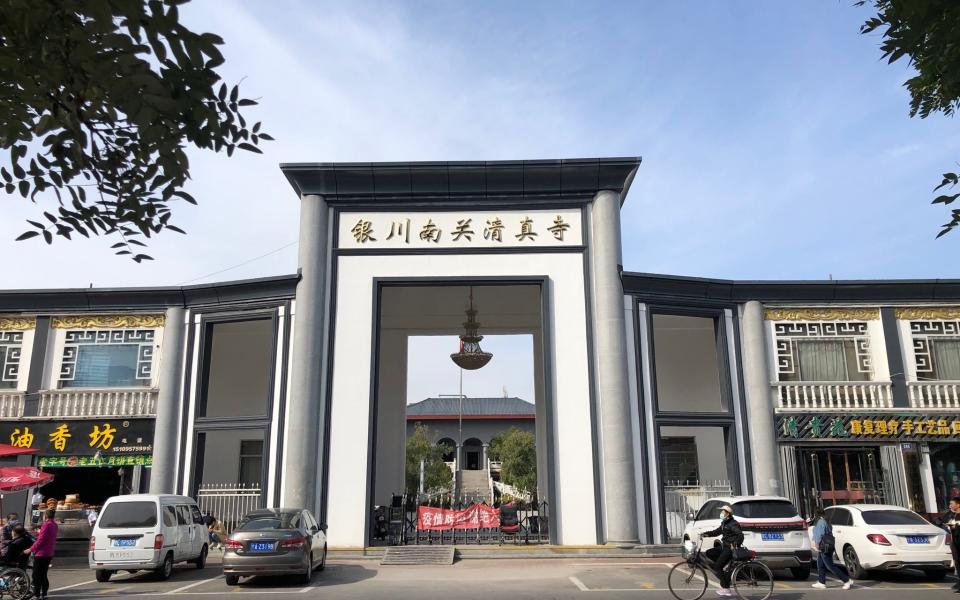

Stark changes have been observed at the main mosque in Yinchuan, capital of Ningxia province, where most of China’s Hui ethnic Muslim minority live.

The bright green onion-shaped domes and golden minarets that used to soar into the sky atop Nanguan Mosque have all been pulled down. Golden Islamic-style filigree, decorative arches, and Arabic script that before adorned the mosque have also been stripped away.

What remains is unrecognisable – a drab, gray, rectangular facility with “Nanguan Mosque” written in Chinese, as shown in photos posted online by Christina Scott, the UK’s deputy head of mission in China, on a recent trip.

“TripAdvisor suggested the Nanguan Mosque in Yinchuan well worth a visit,” Ms Scott wrote on Twitter, along with ‘before and after’ photos. “Only this is what it looks now, after ‘renovations.’ Domes, minarets, all gone. No visitors allowed either, of course. So depressing.”

The UK foreign office said: “We are deeply concerned about restrictions on Islam and other religions in China. We call on China to respect Freedom of Religion or Belief, in line with its Constitution and its international obligations.”

Islamic-style onion domes and decorative elements are also being axed from mosques in neighbouring Gansu province, home to Linxia, a city nicknamed “Little Mecca” for its history as a centre for Islamic faith and culture in China.

Erasing Islamic decorative elements from mosques is yet another step Chinese authorities are taking under Communist Party leader Xi Jinping, who has vowed to ‘Sinicise’ religion.

More recently, the coronavirus has given Chinese authorities convenient cover to keep many mosques closed – even as Beijing crows victory over the pandemic and a flurry of activity has picked up again.

China has for years waged a campaign against Islamic influence, removing decorative elements and Arabic script from buildings, signs and arches, and now, targeting mosques in Ningxia and other provinces.

In Xinjiang, things have taken an especially sinister turn with “re-education” camps that subject detainees to horrific physical torture, political indoctrination and forced labour. Growing a beard, fasting and reading the Koran have all been deemed suspicious behaviour by the government and reason enough to be interned in camps.

Former detainees have told the Telegraph of being electrocuted by cattle prods, made to pledge loyalty to the ruling Party, and of being forced to work in factories manufacturing gloves for little pay.

Schools that previously taught Arabic language and trained imams have also been forced to shutter, the Telegraph has reported. Instead, the government has set up special schools to train imams to have the “correct political stance,” according to Chinese state media.

Chinese authorities are “really worried about external religious influence and authority,” said Dru Gladney, an expert in China’s ethnic minority groups and a professor of anthropology at Pomona College.

Being religious “is a threat to the political authority to the state; you’re giving allegiance to a non-Chinese authority,” said Mr Gladney.

“Whether it’s the Dalai Lama or the Pope, or it’s the head of Falun Gong [a spiritual group], the state won’t tolerate it.”

Pictures of exiled Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama are banned, though photos of Mr Xi are allowed, and encouraged, as observed by foreign journalists on a recent government-arranged trip to Tibet.

“Xi is centralising authority and centralising power,” said David Stroup, a lecturer at the University of Manchester who has studied ethnic minority groups in China.

There’s an interest “to build a nation-state identity,” he said.

Indeed Mr Xi has talked of the “Chinese dream” – an effort to foster a shared identity, a move the Communist Party is betting will secure greater political stability in the long-run.

Experts, however, argue that the suppression campaign in the long-term will backfire.

“They’re creating more resentment among Muslim communities, and theyr’e going to push more of them into more radical solutions,” said Mr Gladney.

Officially, the ruling Party recognises five major religions – Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicisim and Protestantism. But in practice, the government tightly controls and regulates the practise of these faiths.

China, for instance, has long insisted that it approve bishop appointments, clashing with absolute papal authority to select them. Even mentions of “God” and “Bible” have been censored from children’s classics, like Robinson Crusoe, translated for school curriculums instead as “good heaven” and “several books.”

The suppression is not “just targeted exclusively at Islam, but seems to be prosecuted most vigorously when it comes to Islam,” said Rian Thum, senior research fellow at the University of Nottingham.

That is because of broader Islamophobia in China given a misperception that terrorism is linked to Islam, he said.

Another reason is “the turn toward ethnonationalism as a legitimising narrative for why the Communist Party should be the organisation that runs China".

And that is why religions deemed to be foreign are being targeted, he said.

“This is an ethnonationalist purge of cultural material seen as foreign by virtue of not lining up with the Han ethnic majority.”