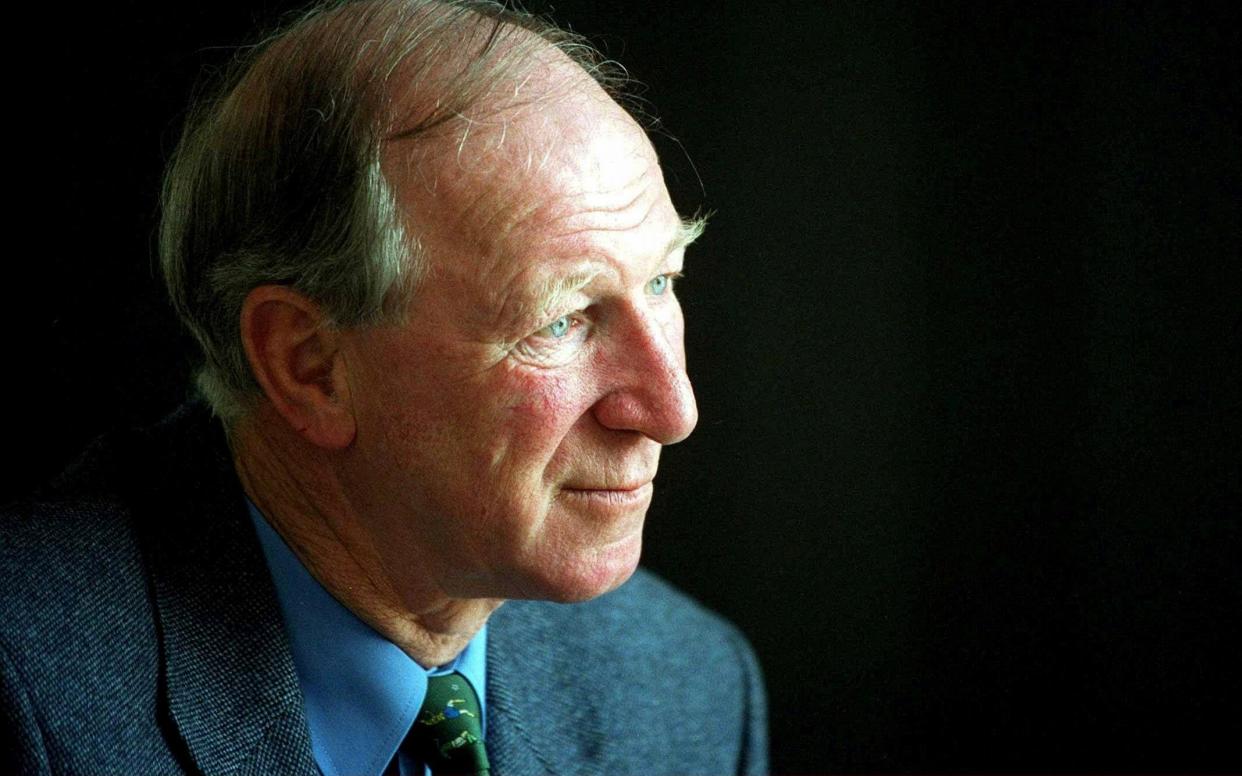

Calls for posthumous knighthood for Jack Charlton as football mourns his death

There are calls for Jack Charlton to be awarded a posthumous knighthood following his death at the age of 85 after a year long fight with cancer.

The former Leeds United defender and Republic of Ireland manager had been diagnosed with lymphoma in the last year and was also suffering from dementia.

In a statement Charlton’s family said he died peacefully at his home in Northumberland on Friday, with his family gathered by his side.

It has long rankled fans that ‘Big Jack’ was never made a Sir, unlike his younger brother Bobby, or their fellow 1966 England teammate Geoff Hurst.

Ian Lavery, the Labour MP for Wansbeck, which includes the Charlton’s home town of Ashington, submitted an Early Day Motion on Saturday calling on the Government to award him a posthumous knighthood, and promised to launch a petition “very soon”.

Mr Lavery said Charlton was “a true legend, a man of the people, and never forgot his working class roots.”

Former Liverpool and Republic of Ireland midfielder Ray Houghton backed the call, telling talkSPORT: "For what he's done domestically with Leeds, winning the World Cup, which he should have been knighted for, I've still never understood that, I think that's an absolute disgrace."

It would require a change in the honours system for a knighthood to be awarded posthumously. There were similar calls in 2016 for the late Bobby Moore, another of the 1966 World Cup winning England team, to be knighted. Despite the support of the then FA Chairman Greg Dyke and a cross-party coalition of leading MPs the campaign did not succeed.

Sir Bobby Charlton was knighted in 1994, becoming only the sixth person to be granted the honour for his contribution to football. Geoff Hurst was knighted in 1998.

Sir Alf Ramsey, the manager of the World Cup winning England team, was knighted the year after their victory.

Premier League games were being preceded by a minute's silence this weekend as a tribute to Charlton, with players wearing black armbands.

'You needed Jack in your team'

To a generation of football fans Jack Charlton - one of the last of the shrinking band of players to have lifted the World Cup for England - was the epitome of the game’s hard men, an imposing presence on the pitch while passionate and humorous off it.

Within moments of news of his death breaking on Saturday tributes began to pour in, an indication of his special place in a game that sets great store by its collective history.

One of the most fitting came from Leeds United - the club with whom Charlton spent the entirety of his playing career - who said he would remain in football folklore forever.

Sir Geoff Hurst, Charlton’s 1966 World Cup-winning team mate, wrote on Twitter: "Another sad day for football. Jack was the type of player and person that you need in a team to win a World Cup.

"He was a great and loveable character and he will be greatly missed. The world of football and the world beyond football has lost one of the greats. RIP old friend."

Greg Clarke, the FA Chairman, said: "A true giant of English football, Jack will forever be remembered for his significant contribution to our World Cup win in 1966 and for being a warm-hearted, thoughtful man.

"I am certain that all football fans, and many more besides, will mourn Jack today. He left an indelible impression on our national game and was guaranteed an affectionate and warm welcome wherever he went. A huge presence on and off the pitch, Jack will never be forgotten at Wembley."

Gary Lineker, the former England striker and Match of the Day presenter, tweeted: "World Cup winner with England, manager of probably the best ever Ireland side and a wonderfully infectious personality to boot. RIP Jack."

Peter Reid, the former England midfielder, described him simply as “a great man”.

Ireland’s unexpected success at Euro 88, reaching the quarter-finals against the hosts at Italia 90 and the 1994 World Cup in the United States - where they reached the last 16 - made him a hero in the Republic at a time when relations between the two countries were still fractious. In 1996 he was awarded an honorary Irish citizenship, being made a freeman of the city of Dublin in 1994.

Ireland's Deputy Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, who remembered watching Ireland beat Romania in a penalty shootout to reach the quarter-finals of the 1990 World Cup, said: "It was a time when in Ireland we didn't have all that much to cheer about or be proud about. I think that really lifted the nation. He was Ireland's most loved Englishman."

Eamon Dunphy, a former Ireland player and pundit, said Charlton managing the Republic's 1988 Euros debut victory over England was a "transformative moment" for national confidence.

"Nobody can prove it and economists would laugh, but I think there are moments like that in a nation's history," Dunphy told RTE. "It transcends soccer and it's part of our folklore now. Jack left an indelible imprint on our life, on our culture and from a soccer point of view, he was a massive evangelical figure."

In a statement Charlton’s family said: "As well as a friend to many, he was a much-adored husband, father, grandfather and great-grandfather.

"We cannot express how proud we are of the extraordinary life he led and the pleasure he brought to so many people in different countries and from all walks of life.

"He was a thoroughly honest, kind, funny and genuine man who always had time for people.

"His loss will leave a huge hole in all our lives but we are thankful for a lifetime of happy memories."

The long years at Leeds, the ‘66 World Cup winners medal, the successful career as manager, of Sheffield Wednesday, Middlesbrough and Newcastle, then famously the Republic of Ireland, might easily have never happened.

Born in Ashington, the epicentre of Northumberland’s coalfields, Charlton’s first job was a miner, going down the pit at the age of 15, like his father - despite being offered a trial at Leeds United, where his uncle Jim was left back.

His brother Bobby, who overshadowed much of his career, was taken on by Manchester United, while several uncles played for Leeds and other clubs.

A cousin of Jack and Bobby’s mother Cissie(see picture below) was the legendary Newcastle United player Jackie Milburn and it was Cissie, not their father, who played football with the children and later coached the local schools team.

Life down the pit did not suit Charlton and after a short spell as a miner he applied to join the police, before reconsidering the offer from Leeds.

He went on to play for them for 21 years, making a joint club record 773 appearances, before retiring as a player in 1973.

For much of his playing career Charlton lived in his brother Bobby’s shadow. After all Bobby had the flair and the goalscoring panache, something Jack was happy to acknowledge.

"I wasn't very good at playing football. But I was very good at stopping other people playing football,” he once said. “My brother was the player.”

Such was his modesty he initially kept his World Cup winner's medal in a coal bucket.

That belied his crucial presence both on the pitch and on the touchline, but it was a measure of his modesty and perhaps a realisation that had his luck been different he might have easily spent his career not on the playing field but in the gloom of the pit.

Now only Bobby, George Cohen, Nobby Stiles, Hurst and Roger Hunt remain of that golden generation who held the Jules Rimet trophy aloft at Wembley.