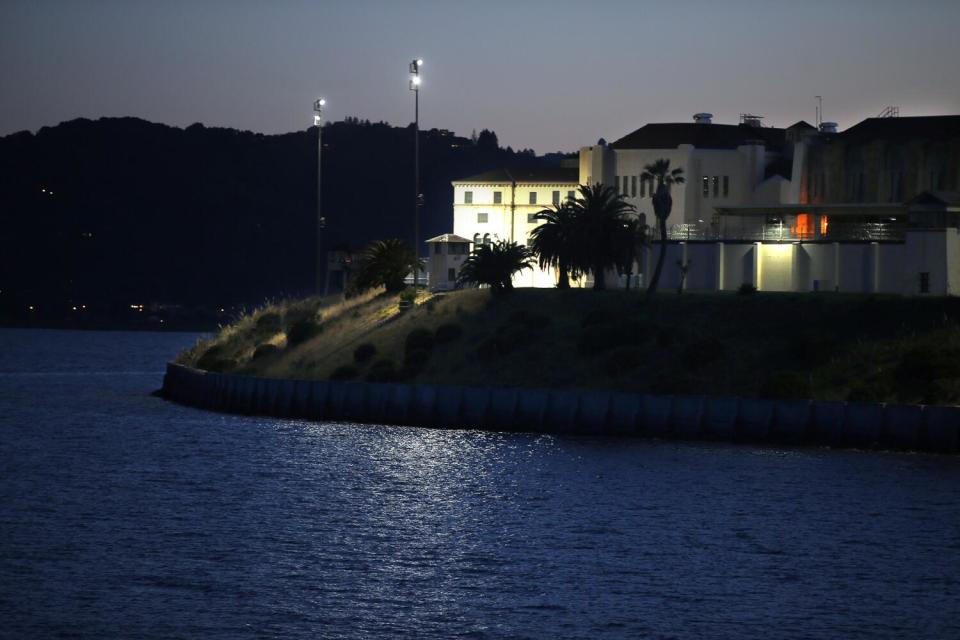

California speeds plans to empty San Quentin's death row

California is accelerating its efforts to empty San Quentin's death row with plans to transfer the last 457 condemned men to other state prisons by summer.

The move comes five years after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order that imposed a moratorium on the death penalty and closed the prison's execution chamber. It coincides with his broader initiative to transform San Quentin into a Scandinavian-style prison with a focus on rehabilitation, education and job training.

The condemned prisoners will be rehoused in the general population across two dozen high-security state prisons, where they will gain access to a broader range of rehabilitative programming and treatment services, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The changes do not modify their sentences or convictions.

The plan unveiled Monday builds on a pilot program that experimented with the transfer of 104 death row prisoners from January 2020 to January 2022. An additional 70 people on death row have been moved from the legendary men's facility in Marin County over the last month, the department said. The 20 condemned women incarcerated at the Central California Women's Facility in Chowchilla will remain there, but have been rehoused in the general population.

The changes align, in part, with Proposition 66, a statewide ballot measure approved in 2016 that allows for condemned prisoners to be housed in institutions other than San Quentin, requiring them to work and pay 70% of their income to victims.

“This transfer enables death-sentenced people to pay court-ordered restitution through work programs. Participants are placed in institutions with an electrified secured perimeter while still integrating with the general population,” corrections department Secretary Jeffrey Macomber said in a prepared statement.

But a primary aim of Proposition 66 was to speed up executions by setting time limits on legal challenges and expanding the pool of attorneys authorized to represent defendants sentenced to death. In that same election, voters defeated a rival measure that would have repealed capital punishment.

By contrast, Newsom vowed in 2019, when announcing his death penalty moratorium, that no California prisoner would be executed while he is in office because of his belief that capital punishment is discriminatory and unjust.

Even before Newsom's moratorium, executions had been on hold in California for years amid litigation over whether the state's lethal injection process constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. California's last execution was in 2006. There are 644 condemned people in California's prisons.

Read more: California to transform infamous San Quentin prison with Scandinavian ideas, rehab focus

Last year, Newsom announced plans to overhaul San Quentin, California's oldest prison, into a more rehabilitative facility with job training, substance-use and mental health programs as well as expanded academic classes, a model of incarceration more common in Scandinavian countries.

But death row prisoners will not be incorporated into the re-envisioned San Quentin. Outside of death row, the facility does not have the necessary security measures, including a "lethal electrified fence," to rehouse high-security prisoners in its general population.

Newsom proposed $380 million last year to jump-start the San Quentin overhaul and set up an advisory council to implement his vision. But, faced with a looming state budget deficit topping $37 billion, lawmakers in both political parties, as well as the Legislature's nonpartisan financial advisors, have raised questions about the scope and timing.

The Legislative Analyst's Office recently recommended closing five prisons to reduce criminal justice spending, in addition to the two state prisons the Newsom administration has already closed. Meanwhile, the San Quentin advisory council in January recommended redirecting some of the money dedicated to the revamp to renovations that would more immediately improve living conditions at the prison.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.