Bruce Lee’s long, violent journey to immortality: ‘He knew the star should always be the boss’

Bruce Lee wanted to be the biggest box office star in the world. He said as much to his friend and martial arts student, Stirling Silliphant. Lee announced that he would one day be a bigger star than both Steve McQueen and James Coburn, A-list actors who were also students of Lee’s. Silliphant – an Oscar-winning screenwriter – replied in the negative: “You are Chinese in a white man’s world. There’s no way.”

Silliphant’s words – more tough love than outward racism – summed up the battle that Lee faced in Hollywood. US executives did not believe that an Asian actor would be a bankable leading man. Lee’s “bigger than McQueen and Coburn” comment (though not the only time he would voice such bold aspirations) came amid frustrations about a passion project, The Silent Flute, which failed to materialise in his lifetime – one of numerous unmade, unfinished or fallen-through projects.

Returning to Hong Kong, Lee revolutionised martial arts cinema with a series of films made under the studio Golden Harvest. The films included The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, The Way of the Dragon and Game of Death, which are in select cinemas throughout June and July – marking 50 years since his death – and then released in a box set of 4K restorations with a five-storey pagoda’s worth of extras.

As described in Matthew Polly’s biography, A Life, Lee was “bigger than The Beatles” in Asia when he died – 15,000 people lined the streets for his funeral – but he was still just “an obscure TV actor” in America. It took the posthumous release of his final film, Enter the Dragon – the first co-production between Hollywood and Hong Kong – to make him a star name in the West. But it went even further than that: Lee transcended to become an icon of the 20th century. “Because of what he could have been,” says Frank Djeng, an expert on martial arts films and a DVD commentary regular. “Because he died so early. He became a myth.”

Stardom was predestined. Lee was a “nepo baby”, says Polly. Lee’s father was an opera singer and actor, while “Little” Bruce – born in San Francisco in 1940 as his father was on tour – was a child star. He acted in 20 films as a kid – weepy melodramas. Polly says that Bruce was “the Macaulay Culkin of Hong Kong”. But teenage Bruce was a handful – a poor student and streetfighter – and was sent back to America. “He went from being upper-class rich in the third world of Hong Kong to a poor immigrant off the boat in the first world,” Polly adds.

Lee taught kung fu to make money. A student himself of the legendary Ip Man, Lee’s approach was progressive. “He was really one of the first Chinese martial artists who spoke English,” says Polly. “He came with this fresh, modern, open attitude. His first student was Black – unheard of at the time.” Rather than stick to the tradition of what was passed down by kung fu masters for 1,000 years, he sought to create the perfect martial art – which he named Jeet Kune Do (“the way of the intercepting fist”) – an adaptable and efficient hybrid that could anticipate attacks and expose the weakness of more rigid systems. Martial arts were very much Hollywood’s fad-of-the-moment. Lee attracted a mix of students, from big-name celebs to tough-as-nails black belts.

In 1966, Bruce landed the role of high-action sidekick Kato in the quickly cancelled TV series, The Green Hornet. Other film and TV roles were few and far between, while projects and development deals collapsed. Now married with two children, Lee needed money. He returned to Hong Kong to make films with Golden Harvest, a fledgling upstart studio run by Raymond Chow. Chow was challenging the rival Shaw Brothers Studio, which had a virtual monopoly over Hong Kong film.

He was in a kind of constant Freudian competition with his father. Clearly, he was driven. Once he got a taste for it, he wanted a bigger mansion, he wanted to be more famous

Matthew Polly

Lee’s first Golden Harvest film, The Big Boss, was released in Hong Kong in October 1971 and broke box office records. The follow-up, Fist of Fury – released in March 1972 – broke records again. Lee’s success tapped into a trend of nationalism among Hong Kongers at the time. In The Big Boss, Lee plays a Chinese factory worker who travels to Thailand and takes on gangsters. In the blatantly nationalistic Fist of Fury, he battles aggressors from a rival Japanese dojo.

“There’s an element of him presenting a strong, dominant, masculine Chinese hero who’s proud of his heritage,” says Djeng. “He avenges racial prejudice. His films would have this social relevance – not just to the Chinese in Hong Kong but also to Asians living in the United States.”

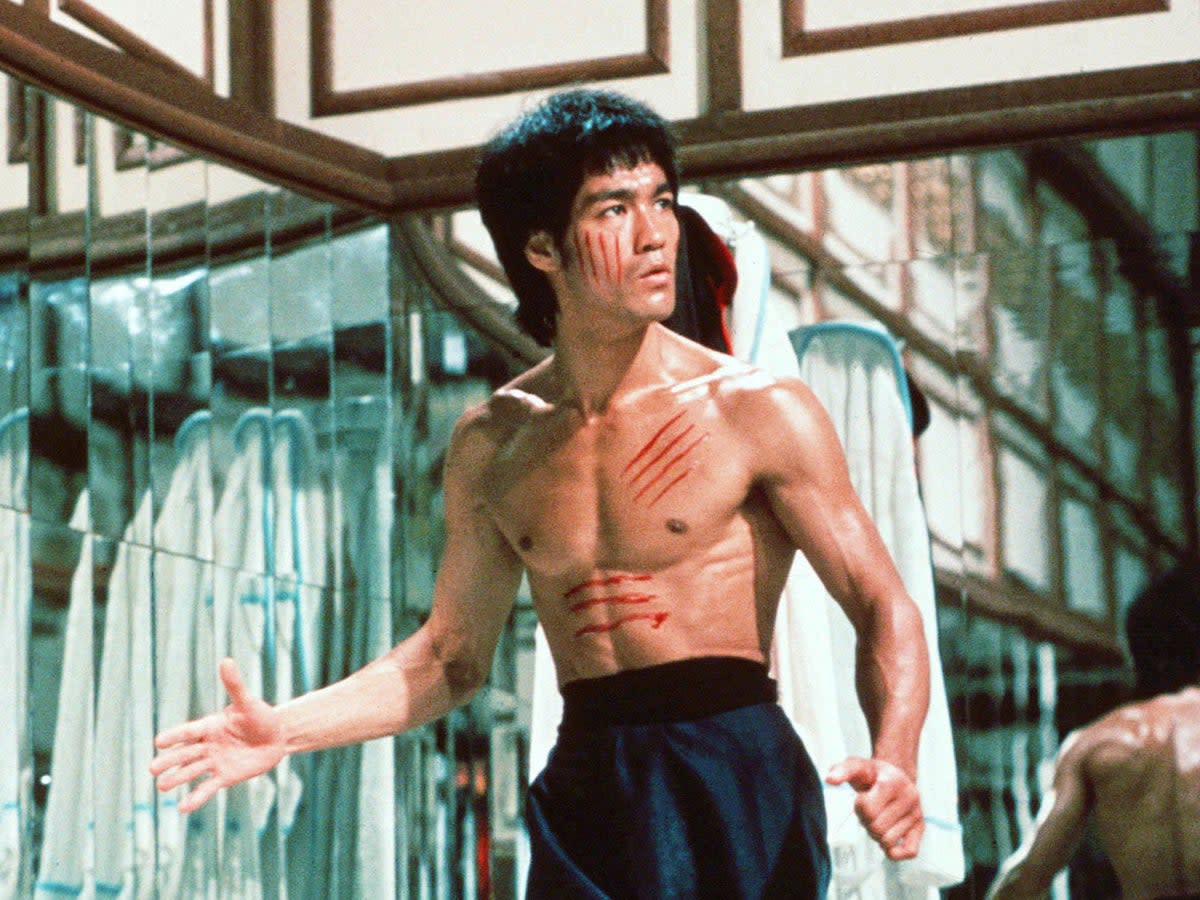

Lee’s films hit hard for another reason: game-changing kung fu. Hong Kong cinema was previously dominated by Shaw Brothers-produced films in the wuxia swordplay tradition – balletic, intricately choreographed action routines. By contrast, Lee’s fights were real – albeit “heightened realism”, Polly says – with speed and believable impact. “Oftentimes it’s Bruce Lee just knocking someone out in a few moves,” says Djeng. He also points to Lee’s psyching-out tactics – the much-imitated yowling cat calls.

Lee also clashed with The Big Boss and Fist of Fury director, Lo Wei. Lee wanted to bring Hollywood production values to the region’s comparatively shabby cinema – he also wanted control over all aspects of his films. “He learnt from Steve McQueen that the star should always be the boss,” says Polly.

For Lee’s next film – Way of the Dragon – he took the roles of writer, director, producer and star. He plays Tang Lung, who travels to Rome to help protect a Chinese restaurant against a local crime boss. To non-kung fu aficionados, The Way of the Dragon is a bonkers film, beginning as a dopey comedy – including a running gag about Lee needing the toilet – that eventually builds to his most iconic showdown. It saw him fight real-life pal and double-hard karate champion Chuck Norris.

“I don’t think it’s ever been surpassed,” says Polly about the Lee versus Norris fight. “What’s interesting is that he’s injecting his own Jeet Kune Do philosophy into that fight. He starts off losing because he’s too stiff and attached to tradition, and then he adapts – he becomes looser and more fluid – and that’s how he beats Chuck Norris. It has a pedagogy underlying the scene, which is rare for a kung fu movie.”

The Way of the Dragon beat The Big Boss and Fist of Fury at the box office. Lee wasn’t entirely happy with it and didn’t want it shown in the West, arguing with Chow when he learned that he was negotiating a US distribution deal (though it didn’t release there until after his death). But for Djeng, it’s also a film that speaks to the real Lee. “Way of the Dragon is my favourite Bruce Lee film,” he says. “You see the transformation of this man who starts out as a nobody – this country bumpkin – going to a land where he doesn’t speak the language. It was a representation of someone who makes his mark overseas. I think that’s what the film is all about.”

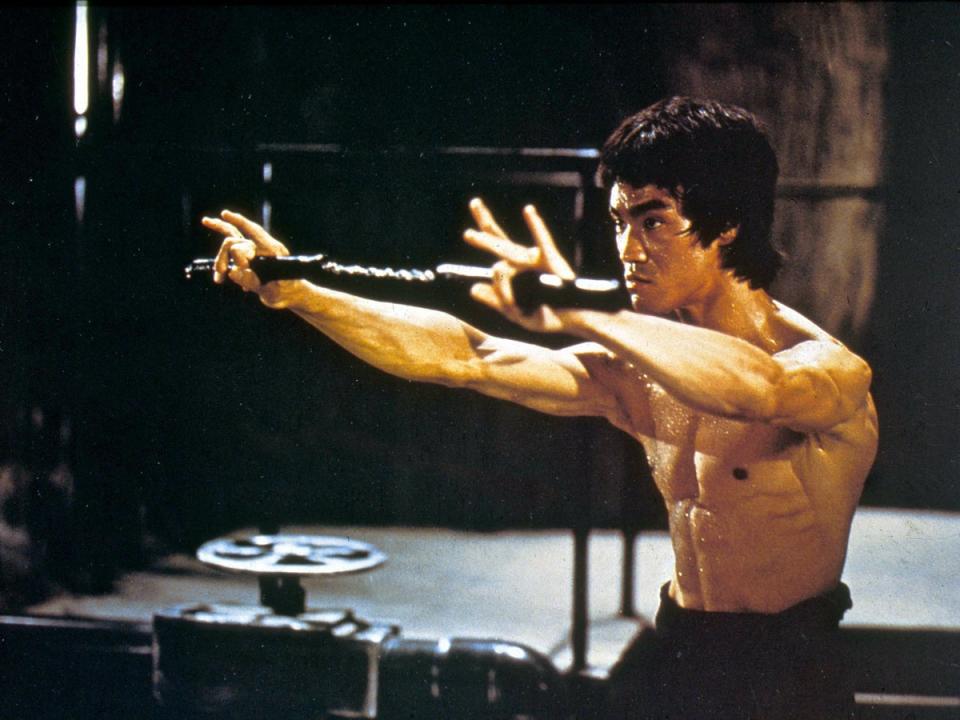

The Jeet Kune Do philosophy – as demonstrated in the Norris fight – would continue in Lee’s incomplete, would-be masterpiece, Game of Death. In the planned story, Lee’s character would ascend a five-storey pagoda and defeat a different enemy, each with a different fighting style, on every level. The final opponent was 7ft 2in basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar – one of Lee’s (very) high-profile students. The casting was significant. “Kareem was using Jeet Kune Do in some way, too,” says Djeng. “It’s almost like Bruce Lee is fighting with himself – which would explain why Kareem is the last fighter.”

Production was paused when Warner Bros offered Lee a chance to star in Hollywood’s first kung fu film: Enter the Dragon. Game of Death was never finished. A reported 100 minutes of footage was shot, with around 40 minutes of usable material. Much of it was misplaced in the Golden Harvest archives, with some rediscovered years later. Rumours have persisted about what footage may or may not exist. A much-talked-about, never-before-seen “log fight” is included on a new 4K set. Though incomplete, Game of Death remains influential.

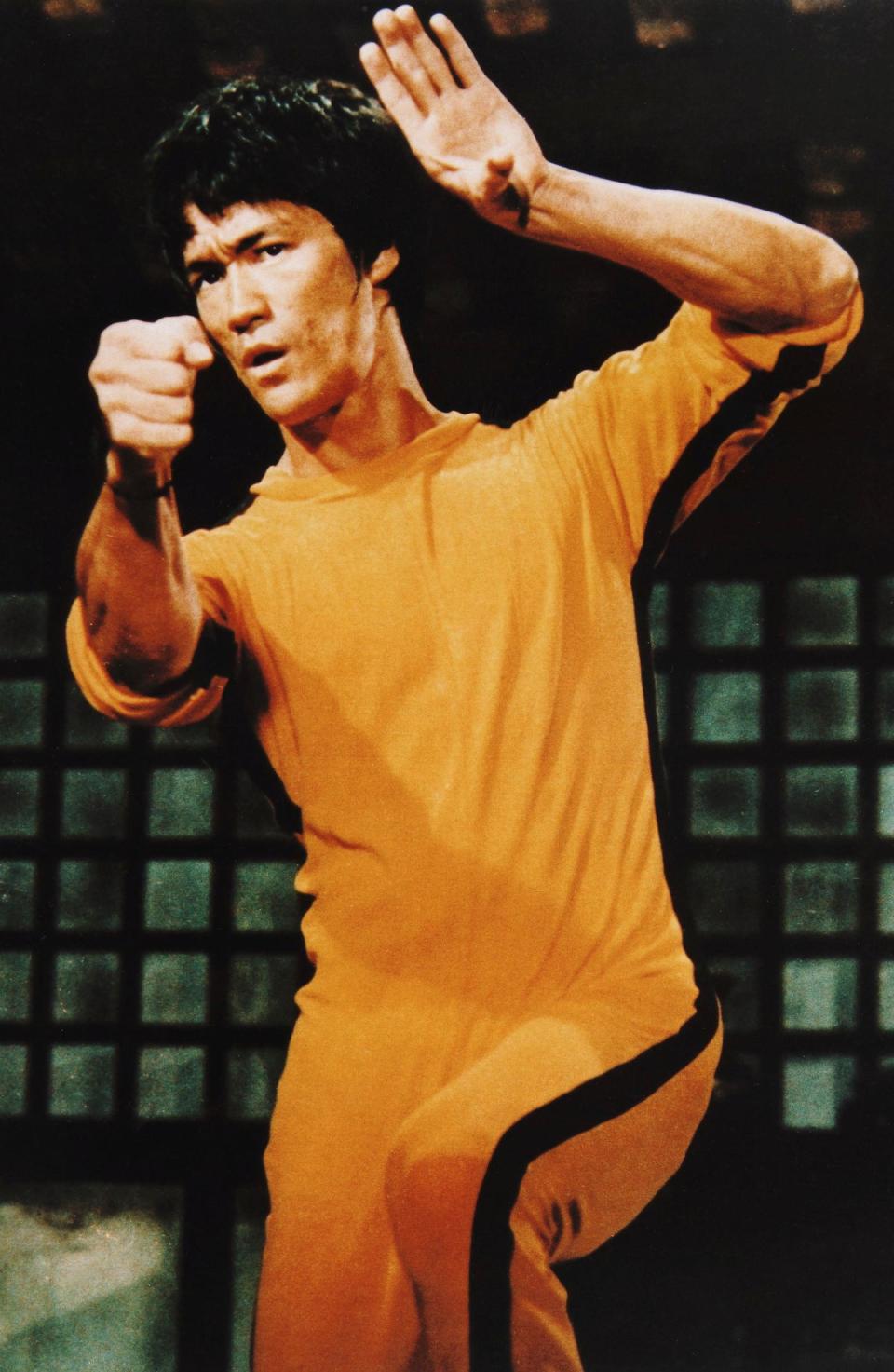

“This idea of ascending a tower while defeating enemies of each level is a precursor to video games,” says Djeng. “It inspired so many action films – Die Hard, Dread, The Raid.” There’s also the yellow jumpsuit Lee wears in it – the inspiration for Uma Thurman’s similarly-styled duds in Kill Bill.

Lee’s breakout success in Hong Kong was intense. He had a tricky relationship with the tabloids, which gave him the build-‘em-up-then-knock-’em-down treatment and exploited a tension between his Chinese and American sides (not only was he born in the US, his mother was Eurasian). But what drove Lee to become a megastar? Money? Fame? Pride? The 2000 documentary A Warrior’s Journey suggests cinema was a platform to share his martial arts philosophies.

“My theory is that he was in a kind of constant Freudian competition with his father,” says Polly. “Clearly, he was driven. Once he got a taste for it, he wanted a bigger mansion, he wanted to be more famous. Add to that the racism he endured in Hollywood – not cruel but dismissive. The injustice of that drove him as well.”

Around the same time, Lee lost the lead in the US TV series Kung Fu. Execs thought his accent was too thick. The role went to white actor David Carradine. As Polly also notes, Lee had tried to straddle both East and West. For mainstream Hollywood audiences, Enter the Dragon is Lee’s easiest watch by far. Directed by Robert Clouse, it’s a deliberate James Bond knockoff: Lee’s character is enlisted by a British spymaster to infiltrate a martial arts tournament, hosted on a secret island by a claw-handed crime lord. “It’s the only one made in English with Hollywood production values,” says Polly. “And with a plot that’s understandable to a Western audience. You can kind of imagine what Bruce Lee would have been like as a Hollywood star. You have to be a real kung fu head to enjoy his other movies.”

Lee died on 20 July 1973, aged 32. He died in his mistress’s bed, which Raymond Chow initially tried to cover up. The coroner’s verdict was cerebral edema (swelling of the brain) but its cause was never determined. Polly convincingly theorises heat stroke. “But to this day, there’s no consensus on how he died,” he admits.

The more scandalous elements of Lee’s death – the mistress, the deception, the traces of cannabis found in his system – caused a tabloid frenzy. And there were wild theories: Lee was poisoned; Triads killed him; he was oversexed; he was cursed. “People were taking bets on whether it was a publicity stunt for Game of Death,” says Polly. Nothing says “20th-century icon” like dying young and leaving a trail of faked-death conspiracy theories.

Enter the Dragon was released the following month. It made $90m (£72m) in the US and began a worldwide craze. In Hong Kong, however, it didn’t fare as well. Djeng thinks that Enter the Dragon sidelined Lee too much – focusing instead on American co-stars John Saxon and Jim Kelly – and features negative, amalgamated stereotyping. “For me, the most egregious offence is having all the fighters on the island and they’re all wearing karate robes!” he says. “This is supposed to be a Chinese kung fu thing. It’s like they’re putting everything that’s ‘oriental’ into the film. I think the Hong Kong audience felt offended.”

Next came a cycle of posthumous “Bruceploitation” films, which starred Lee lookalikes – including Bruce Li, Bruce Le and Dragon Lee – who mimicked his fighting. (Djeng has co-produced an upcoming documentary on the phenomenon, Enter the Clones of Bruce.) In 1978, Raymond Chow released the ultimate Bruceploitation flick: a reworked Game of Death, which used 11 minutes of Lee’s original footage and padded out the rest of the runtime with Lee stand-ins, a cobbled-together story and – rather ghoulishly – footage from his funeral. Game of Death II followed in 1981, using scraps of footage from Enter the Dragon.

A fascinating thing about Bruce Lee is that so many of the legendary tales – the one-inch punch; the two-finger push-ups; beefing with other martial artists; being challenged by stuntmen; having his armpit sweat glands removed – are true. But the incompleteness of Game of Death best encapsulates Lee’s icon status. “His life was incomplete,” says Polly. “We had to imagine what he would have been.”

‘The Big Boss’, ‘Fist of Fury’, ‘The Way of the Dragon’, ‘Game of Death’ and ‘Game of Death II’ are all being released in cinemas across the UK from 2 June into July. The accompanying box set – featuring exclusive 4K restorations by Arrow Video – is available from 17 July