Before Borat: meet the anti-PC French clown who taught Sacha Baron Cohen to be funny

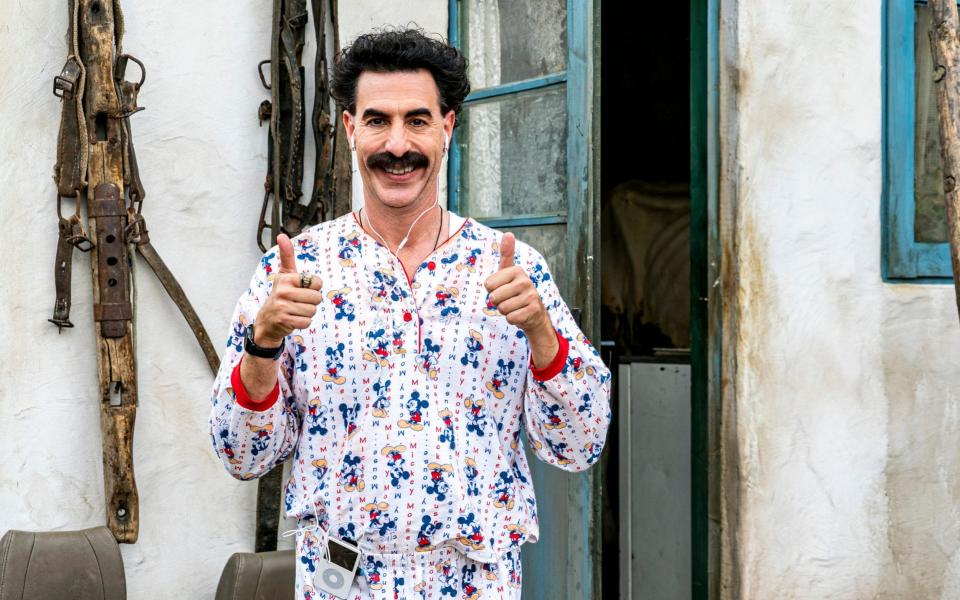

Whether you’ve laughed or winced, the chances are that if you’ve watched Borat 2 – or rather Borat Subsequent Moviefilm – there will have been moments when you thought: where did Sacha Baron Cohen find the confidence, the chutzpah and the clowning wherewithal to pull off these stunts?

How did he get to a place where he could assail Rudolph Giuliani in a hotel suite wearing a pink bra, panties and a ludicrous wig and barrack him, in a preposterous foreign accent, with such lines as: “She 15, she too old for you.. take me instead”? Or go on stage at an anti-lockdown rally and commandeer a sing-along (“WHO – what are we going to do? Chop them up like the Saudis do!”)? You can’t teach that kind of thing, can you? Perhaps you can.

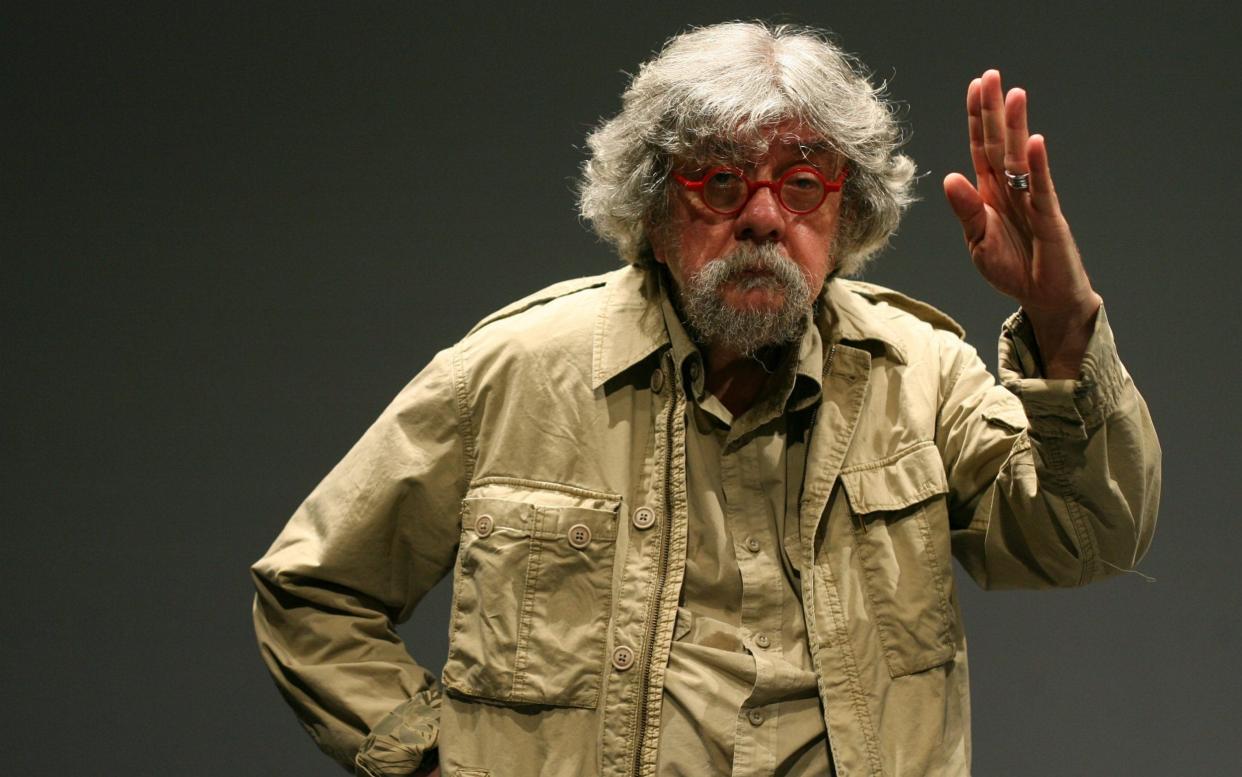

Baron Cohen has attributed his achievements to now 77-year-old French theatre guru Philippe Gaulier. In 2001, the star – then best known for Ali G, and still developing the character of Kazakh reporter Borat Sagdiyev – described Gaulier as “probably the funniest man I have ever met” and stated: “Without him, I really do doubt whether I would have had any success in my field.”

Born in occupied Paris in 1943, the son of a doctor, Gaulier came to attention as a teacher of clowning at the school of Jacques Lecoq (1921-1999), considered one of the founding fathers of modern physical theatre. He set up his own school in Paris in 1980 and relocated it to the north London suburb of Cricklewood in 1991. It was around five years later that Baron Cohen – who graduated from Cambridge in 1993 – attended and seems to have found his funny bones.

In assessing what role Gaulier may have had in the ‘making’ of this outrageous latter-day Peter Sellers, it’s worth observing that Baron Cohen is far from the only household name to have benefitted from classes in clowning and other theatrical arts at his venerated establishment. The Oscar-winning Roberto Benigni ranks as the best-known of Gaulier’s legion non-British international students. American Phil Burgers, aka the silent comedian Dr Brown, who won the Edinburgh Comedy Award in 2012, is another notable alumnus. But British talent has flourished especially noticeably under his tutelage.

They include director Simon McBurney, who went on to co-found (and now runs) Complicité, comedy duo The Right Size (one half of which, Sean Foley, now runs Birmingham Rep), Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter. Without the impact of Gaulier on actor turned director Cal McCrystal, who first went to study with him in 1988, the National mightn’t have had such a hit with One Man, Two Guvnors, which enabled James Corden to bounce back to prominence in 2011 and soar higher than ever. Belfast-born McCrystal – who tended to the show’s physical comedy, and has worked with Baron Cohen – says Gaulier “has had a huge influence on British comedy through people carrying on their version of his teaching.”

What is it that he teaches, exactly? The response when I phone the great man himself at his base on the southern outskirts of Paris, Etampes, is light on specifics but has a simple core philosophy. “The teacher helps the student to discover something of himself. We don’t give spirit to the student, we help the student to find it. “Sacha”, he continues in his faltering English, “has a great spirit. If you have crazy things in your head, it’s better for you.” He’s modest about his own contribution, then? “I don’t feel proud. That’s not my job. It’s about helping people to discover something in themselves.”

These sentiments haven’t altered since I met him in 2001 when he affirmed: “I don’t teach a special style… People have to find a way of being beautiful and surprising”. His definition of beautiful is “anyone in the grip of pleasure or freedom”. That act of liberation isn’t achieved without cost. Gaulier has a mythic reputation for his brusque treatment of students who must try, and try again, in class to avoid anything that answers to the dread assessment of ‘boring’ or ‘’orrible’.

To watch Gaulier in pedagogical action – witness a valuable (YouTube available) Newsnight encounter with him in 2015 – is to behold a bespectacled, bearded figure surveying his charges with heavy-lidded, unimpressed eyes. “Absolutely awful – there is nothing here,” he scoffs at one duo, dashing hope from their faces. He rhetorically consults the class on the floor beside him, “Money back? Goodbye, goodbye!”

The inventiveness of his put-downs suggests uncommon levels of boundary-pushing. One alumna, the stand-up comedian and actress Elf Lyons, recalls being there days after the massacre at the Bataclan theatre in Paris in 2015. Gaulier reassured his shaken students: “OK, today we make no jokes about being shot with guns”. No sooner was he starting on his pupil-criticism, though, than he sniped: “'Do we wish they were at the Bataclan?' Everyone burst out laughing – just as a release of tension after the horror of what had happened. But some would find that [joke] problematic,” Lyons admits. “When he says ‘you are horrible, you are disgusting’ he doesn’t mean it. It’s so evidently a game, but performers can be vulnerable.”

Baron Cohen describes Gaulier’s egotism-dismantling tendencies as character-building: “During the time I studied with him he was brutally honest, constantly reminding me of when my performance was rubbish and very occasionally telling me when it was not so bad”. John Wright, who co-founded the theatre company Told By An Idiot, has described the approach as “open-heart surgery without anaesthetic”. For McCrystal the lack of kid gloves is the essential helping hand. “Putting yourself on the line and trying to be funny is the hardest situation to be in and what you don’t want to happen when you fail is for someone to say: “Well done for trying, bless you.” You can start again –forget what you know and find the most stupid part of yourself.”

“I don’t know if I am rude,” the expletive-prone Gaulier reflects today. “But I am funny. People don’t leave the class because I’m boring. It’s better for a teacher to be rude than like a fresh cream from Normandy. Now we have to be politically correct but I’ve never been politically correct. I love to say horrible things – I get that from my mother. She was from Spain and the Spanish have a black humour. They say “f--k you” to many people, the Spanish. Lecoq never said vulgar things. That’s why the students loved me there, and why they love me today. To be rude is part of the pleasure of life – not to be nasty. Though with some students I am happy to be a bit nasty.”

That defiant attitude appears to have started early. “My father was a bourgeois idiot,” he says “and I was the rebel. I said f--k you to the bourgeois family”. He isn’t interested in simple épater la bourgeoisie tactics, though. He disdains the use of nudity. “It isn’t my cup of tea. I don’t give a sh-t unless the idea is funny. With Borat, it’s funny because the guy looks so nasty, and he always has so many ways of saying “F--k you to the American people”.”

Here, we’re alighting on one of the crucial distinctions that has to be made in respect of clown types. In the past Gaulier has described Baron Cohen as a ‘good clown’ but the star’s achievement is to have brought the dark comic energy of the ‘buffon’ (French for buffoon) into the mainstream.

Gaulier indicates the difference thus: “A clown is not grotesque. He wants to imitate adults to make us believe he is intelligent. The buffon is intelligent and he comes to say f--k you to society.” While we’re familiar with the term ‘buffoon’ (deriving from the Italian ‘buffare’, to puff or swell), Lecoq developed particular ideas about this type of mocking fool, found in a chapter in his book The Moving Body – “Bouffons deal essentially with the social dimension of human relations, showing up its absurdities. They also deal with hierarchies of power, and their reversal.”

Lyons walks us through a trio of Gaulier's ‘bouffon’ exercises (none of which involve, as his clowning workshops sometimes do, donning a red nose). “In one, everyone has to come on stage and impersonate a bastard. A bastard is someone Philippe would describe as a person who would give names to the Gestapo – students would impersonate an old teacher, a politician, usually someone who has a sense of power or authority. He will ask you to push it and push it. Another involves one student going on stage and another impersonating them behind their back in such an exaggerated way that the audience laughs at the mockery.

“A third has you telling a horror story but on top of that you have to have some kind of tic – maybe one of your legs shoots out in front of you or you blow a raspberry in the middle of a sentence. As you tell the tale the tic becomes increasingly prominent. The object is that even if the tic is over the top, it mustn’t take away from the story. I think you can see a link with how Borat makes serious points about racism or homophobia while getting ever more ridiculous.”

McCrystal elaborates: “The clown loves the audience and wishes to be loved in return. The buffon goads the audience and makes them laugh at themselves without realising it. There’s a medieval tradition of the deformed and outcast being allowed to return to their villages once a year – the idea being that they would scare away evil spirits. The reward was that they could go into the church to blaspheme and take the piss out of the villagers on the way, seeing how far they could go before they were pelted with stones. And that’s what Borat does. The clown uses the stupid version of their personality to get laughs, the buffon uses the more wily antagonistic side – you’re using different sources to get the same effect, which is laughter. Not everyone has Sacha’s qualities but I think that his fearlessness was engendered by Gaulier.”

“After you study with him, you’re dying to do your own show,” he continues. “When you leave drama school you’re dying to be in someone else’s – that’s the difference.” McCrystal was a consultant on Cohen's 2012 film The Dictator and proffers a behind the scenes glimpse of the obsessive jester-prankster at work. “He’s surrounded by his writing team and other people and everyone is shouting ‘Sacha don’t forget to do this”. He does a lot of takes and what you get is pure gold but it’s not an easy environment to work in.”

The Gaulier environment, too, isn’t always an easy one to study in. Not that there’s a shortage of those willing to brave the school (there are no auditions). It has reopened this autumn, with a reduced number of students (under a hundred, owing to the pandemic) – and will celebrate its 40th anniversary in a delayed fashion, next year. He has no plans to retire. “I don’t want to be bored at home. The job isn’t disagreeable – and I made it myself!”

Do we need clowns more than ever in our Covid-shaken world? Gaulier bats away the idea as too simple. “I don’t know what we need. And nobody knows what we need. If we see a clown coming, then we need the clown but it’s the artist who decides. To say ‘what we need’ is to put the police in art. I don’t like the police so much.”

Borat Subsequent Moviefilm is on Amazon Prime now