Blues Great Buddy Guy on His ‘American Masters’ Documentary, Hitting the Road Again at 85, and Why the Blues Is Like Golf

Damn right, he’s got his own doc. Buddy Guy, the blues legend whose 1991 “Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues” firmly established him as part of the form’s upper firmament after decades of work, is the subject of a two-hour “American Masters” documentary premiering this week. (Besides being seen on PBS broadcast stations, it can be seen on-demand on the PBS app and at this web page.)

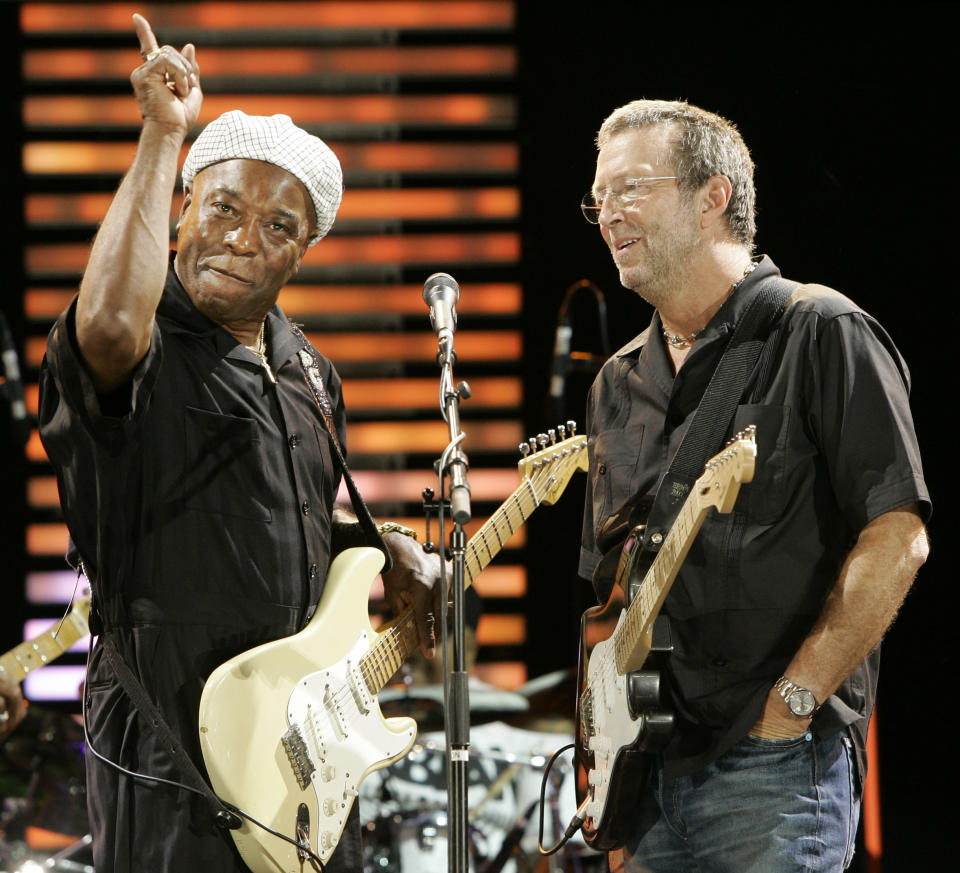

It’s a big week for Guy beyond the documentary: He turns 85 on July 30. In August, he’ll be back on the road for a national tour that takes him into April 2022. That represents a chance to see living history that encompasses, in one figure, membership in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (he was inducted in 2005 by Eric Clapton and B.B. King), celebration by the Kennedy Center Honors (President Obama helped do the honors in 2012), a National Medal of the Arts (bestowed by Prsident Bush in 2003), a Grammy lifetime achievement award (2016) and many more. But as he tells Variety in this Q&A, there’s a marker out on Louisiana Highway 418 that may mean more to him than any of the other kudos.

More from Variety

B.B. King's Estate Responds to Drake and Lil Wayne's 'B.B. King Freestyle' (EXCLUSIVE)

Massive Fraud Alleged at Baidu-Targeted Chinese Streamer YY Live

VARIETY: When you were approached to do this “American Masters” documentary, were you thinking, yeah, it’s about time, or is it that big a milestone for you?

GUY: Well, you know, I was kind of surprised. My friend Bobby Rush and myself were speaking yesterday about all of my friends who are gone who I learned everything from. I didn’t learn nothing from a book. I learned from the Lightnin’ Hopkins and Muddy Waters and the B.B. Kings — all of ‘em gone. So you’re always surprised. My mother used to tell me, “Better late than never.” Whatever you can give the blues a lift with, I’m for it, because blues has been treated like a stepchild. Now, hardly none of your big FM radio stations will play blues anymore. I love all music, but at least let me hear Muddy Waters once or twice a month, you know? So whatever little help I can give with the blues is certainly appreciated from my end of it.

You’ve got like a really substantial tour itinerary coming up, starting in August, and going through next April. As you said, there are not many of the original greats left. Do you feel like you get strong attendance at your shows because people realize that you represent an important part of history that they need to come see?

I don’t know. You know, all of my life, when I go to play a concert, if I’m broke, I’m always worried about: Is anybody coming to see you? But like I said, whatever I can get from you or whoever else to help the blues — not just the Buddy Guy blues. I just want to hopefully be a role model and have some young person come along (to be inspired) like I was with Muddy Waters. When the blues was in the heydays of the Muddy Waters and the B.B. Kings and the Lightnin’ Hopkins and the Little Richards and all that, before we got all these different names of different types of music — everything was R&B back in the ‘40s and ‘50s — it worries me now because blues to me is being ignored compared to the rest of the music. Last night, a hip-hop band asked me to play with them. I sat in, and I said, “What do you want me to play?” “Play Buddy Guy.” And they was all happy about it, because my youngest daughter is into that, and I’m into all music, man. But I’m trying to hope my little words will be heard somewhere so the blues can stay alive a little longer.

You’ve got a lot of great statements about the blues in this documentary. One of them is about the eternal contradiction or irony, when you say, “You play ‘em because you got them, but if you play them, you lose them. … The blues chase the blues away.” Is that something you experience every night, touring?

When I go to the stage, I forget I’m Buddy Guy. Because if the people thought enough of me to come see me perform, I look at faces, if I can see ‘em. And sometimes you can look out there and see a frown. Sometimes you can look out there and see a smile. And that one guy smiling, I hope to keep him smiling, but that one with that frown on his face, I’m working on him. I’ll say, sooner or later, I’m going to hit a lick or say a lyric to make you smile and get that frown off your face. And that everyday-life blues we sing about…. I learned that from Muddy Waters, Little Walter, all those guys who dedicated their lives to the blues. Most of them — Arthur Crudup, Son House, Fred McDowell, all those guys before Muddy Waters — they never made a decent living playing the blues, but they had fun what they was doing. And if they played well enough at one of them Saturday night fish fries, at a house party or something, if you played well enough, they bought you a drink. And if you really played well enough, you got you a good looking girlfriend, and woke up the next morning with a headache, but you had a good time.

How has the audience changed for what you do over the years, and their understanding of what it is you do and sing about?

I think some people may not realize that it’s almost like this COVID-19 we’ve got now. Some people don’t believe it’s for real, still, and it’s killing people. And some people don’t realize what we’re singing about is real. You’ve almost got to be my age to know. It’s something that we go way back with, when we sing some of the lyrics about what was happening to most of the Black people before the British started playing the blues.

I don’t know if you’re old enough to remember in the ‘60s when this television show came up called “Shindig.” The Rolling Stones was making big hits, man, bigger than bubblegum. And “Shindig” was trying to get them to do the show, and Mick Jagger said, “I’ll do it if you let me bring Howlin’ Wolf.” They said, “Who the hell is that?” This is America that told him that. And he got offended. He said, “You mean to tell me you don’t know who Howlin’ Wolf is?” And that just lit me up, man. This man had to come from the British and tell America who we were. They didn’t want to lift us up. Before the British started playing the blues, I think it was 90%, 95%, 98% Black listening to blues. After they started playing, and when I play now, it is 95% or 98% white people listening to blues.

Now that you’re about to turn 85, obviously, one of the great things about the blues is it doesn’t matter whether you’re a young person or older person, people still want to hear you play it. But did you imagine yourself being 85 and out on the road and still doing this?

Well, I can’t jump off the stage like I did 20 or 30 years ago. But blues is like golf. You know, when you’re a prize fighter or football player or a baseball player, after you get to a certain age, you ain’t as fast as you used to be. But a blues player is like a golf player. Blues players and golf players can last a little longer than anybody else, because it’s not a thing that you’ve got to use that youth and that young man’s energy to perform.

And I always did watch my older friends. I’m so proud I got a chance to know ‘em before they passed. Fred McDowell, Son House, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf: They played it until they left here, and they were still playing it very well.

These last few days, I’ve been interviewed by the international press. I tell them, do you know the last time I spoke to the international press? It was when they called and said, “How do you feel that Muddy Waters has passed?” The late Junior Wells and I had just talked to Muddy two days before that, and we heard he wasn’t feeling good. He answered the phone, and he said, “Man, I’m doing fine. Don’t y’all come back here. Just keep the blues alive.” He didn’t want us to know how sick he was because he was still doing the blues. With John Lee Hooker, they called me. I was on tour in Canada and they say, “What do you think? John Lee passed. He played last night, went to a restaurant and ate, went home and didn’t wake up.” And what a way to go. And I hope I’ll be like that.

I’m going to try to do the blues until I can’t do it no more. Even though, at 85, I can feel it. I don’t have the youth that I had that 30 or 35 years ago. But I still can play you a blues song you might want to listen to, or maybe you don’t. And the ones that never heard me might say, “Oh, well, I’ll go see him, because he’s the last, [after] some of the greats who left him here.”

AP

When you look at the kind of tour itinerary you have coming up over a nine-month period, does that make you feel tired or energized?

I’m not really tired. I can’t do it as fast and accurate. But I didn’t never think I was a good enough guitar player. The late, great Guitar Slim was a showman, and I kind of got my ideas from him. As a youngster, I always just said I wanted to play like B.B. King, but I wanted to act like Guitar Slim, because I wanted to get some attention. And when I came to Chicago, September the 25th, 1957… I still don’t think I’m good enough to be talking to you about the blues now. But I guess I must’ve been doing something right, because a lot of the British super guitar players and other people gave me credit for some of the licks I was playing behind Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, whoever made a record. I never did have a big record back then, but I was playing little licks behind Coco Taylor and people like that studio.

The “American Masters” has so many life and career highlights. We know that winning the Grammys, when that first happened, meant a lot to you. But in terms of most memorable nights, playing the White House was a big thing, and having Obama sit in… would that be your most memorable night as a performer, or is there something that surpasses that?

Well, that’s one of them, because you don’t dream of things like that. You know, it’s a tossup with B.B. King and Muddy Waters calling me on stage to play a few licks when I’m like 21 years old, and I said, “Why are y’all calling me?” That was almost as exciting as it is for Obama to invite me to the White House. By the way, I got invited to the White House by President Bush, before Obama, but I didn’t play for him. It was a medal that I received. The Obama one is one that I don’t even know how to explain, but it was definitely unforgettable. And it was also unforgettable for B.B. King to say “Come on up here and play with me,” and Muddy Waters was saying, “You better get on up here before I slap the hell out of you.” Things like that I will carry with me the rest of my life.

In the movie they have you go back and revisit sharecropping days. Is that something you still have a really strong sense memory of, from when you were a boy? Or does it feel like somebody else’s lifetime for you to go back and revisit that?

Well, I hope I’m answering you right. My mom and dad were sharecroppers out on the farm in Lettsworth, Louisiana. And I got approached by the people who give you historical marks, and I said, I want to go back out there where I was born, which is hardly nobody out there now. All of my uncles and aunties and everything on both sides of my family are dead and gone. I said, I would like to see (it on) that highway where I grew up at with no shoes, no running water, no electricity, lamplights. And they named that highway after me on December 8th, 2018, and that’s one of the moments… I don’t know how to explain that compared to the Obama and the Muddy Waters and B.B. King (moments). Because the white kids that grew up with me, who the plantation belonged to, their mom and dad are dead and gone, but they’re still alive. And they let me put the sign right in front of one of their houses, that this is Buddy Guy Way now. That’s the name of the highway.

You know, I don’t have a high school education. There wasn’t even no school out there for Black people. My little grade school was in a church. And when I got up close to it, I said, I don’t care if nobody knows (where this is). I wanted where I was born to have it. I could’ve said put it in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where I grew up as a teenager. And I could have said, put it in Chicago. But I wanted it out there where I was born and raised, when I had didn’t have no shoes. Because the temperature stayed warm down there; only in December, I think, did we see a little snow every four or five years, and otherwise you didn’t have to put no shoes on. All the summer long, we went barefoot. … When I went to look at it and they’ve got the signs up there, you know, something like that is a dream come true that you never dreamed.

Best of Variety

Celebrate 'Jungle Cruise' With the Best Disney Parks Gifts and Merch

Best Gifts, Shoes, Games and Merch to Celebrate 2021 NBA Playoffs

The Most Unique Chess Sets For Every Type of Pop Culture Junkie

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.