Behind The Boy and the Heron: The myths and magic of Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki

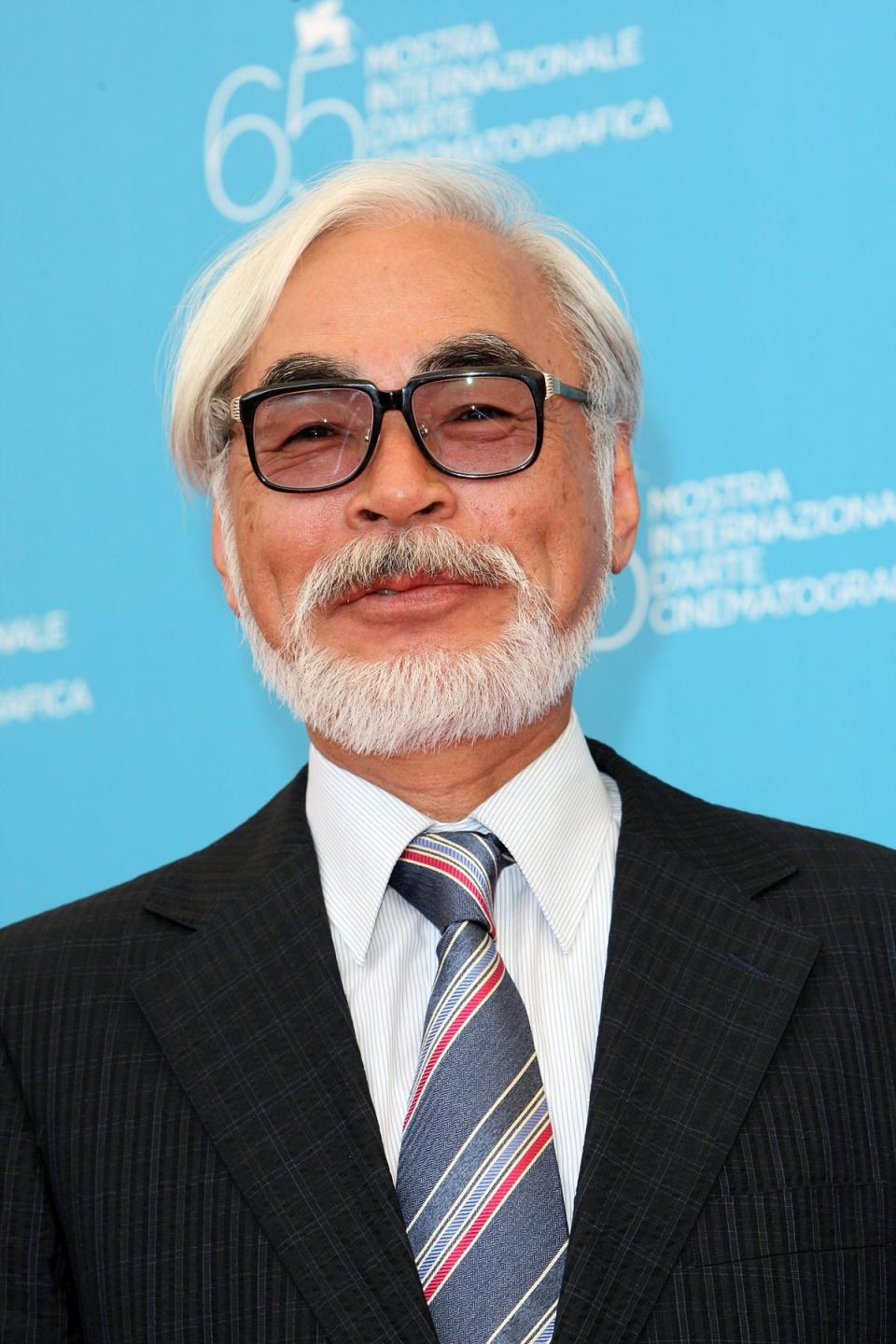

How does a film that shunned all advertising break records in Japan, end up No 1 at the US box office, and become a serious awards contender? Because it’s a Hayao Miyazaki film. If you don’t know the name, make no mistake – this is a big deal. Miyazaki is the talismanic co-founder of Japanese animation house Studio Ghibli, and his latest film, The Boy and the Heron, is finally out in the UK. Up until the day of the film’s premiere, no one had seen a frame of it. In other hands, this marketing strategy would be tantamount to commercial suicide. For Miyazaki, the mere fact of his involvement was advertising enough.

Few artists have ever loomed quite so large over an art form as Miyazaki in the world of animation. His films – lyrical, soulful, endlessly imaginative fantasies – have been pivotal in bringing anime to audiences around the world. His are the films that have made Ghibli a phenomenon: the elegiac epic Princess Mononoke, in which human industrialists go to war with the gods of the forest; the playful, contemplative children’s fantasy My Neighbour Totoro, in which two young sisters encounter a benevolent spirit while their mother is ailing; the utterly unique, Oscar-winning Spirited Away, in which a girl mixes with the creatures and ghouls within a paranormal bathhouse. While other animators have also directed films under the Ghibli umbrella – most notably the late studio co-founder and Miyazaki’s erstwhile mentor Isao Takahata – it is Miyazaki’s name that is synonymous with the studio and its magic.

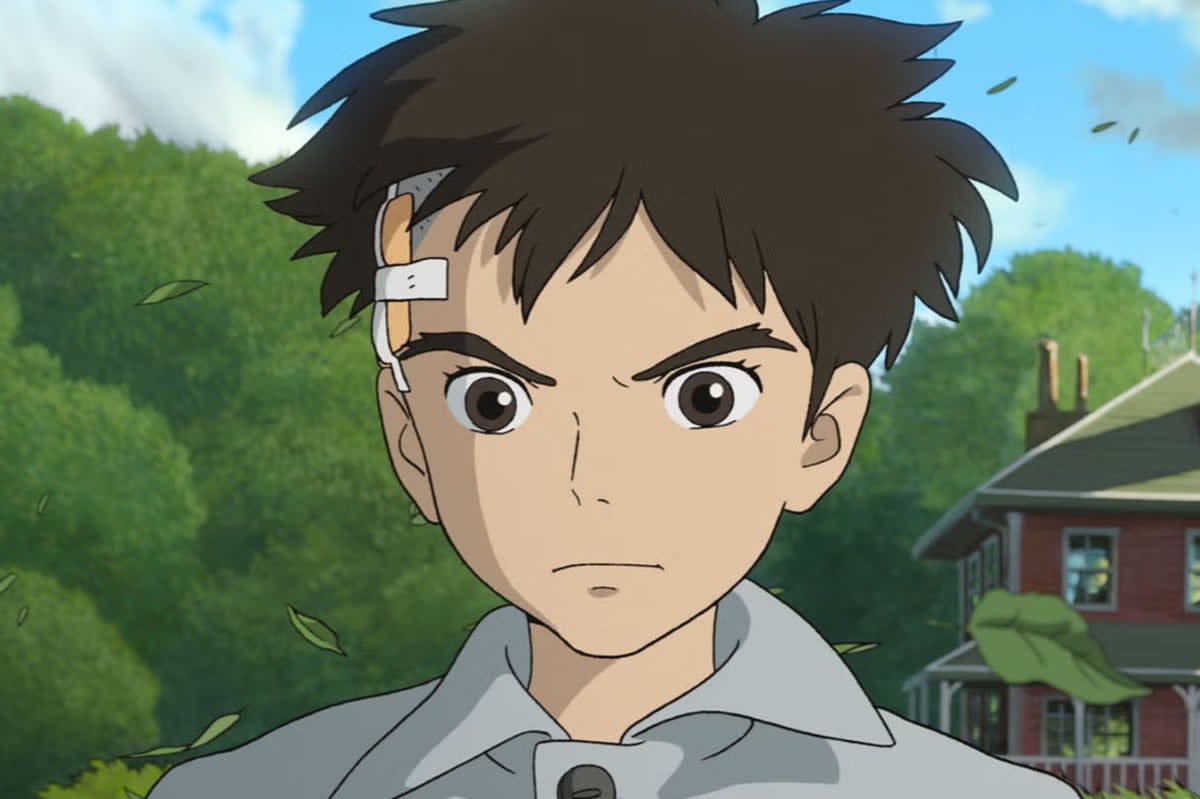

The Boy and the Heron tells the story of Mahito, a child who moves to the country after his mother dies in a hospital fire, only to discover a magical universe inside a nearby mansion house. The film’s starry English-language cast includes Robert Pattinson (doing a berserkly unrecognisable voice), Florence Pugh, Dave Bautista, Christian Bale and Willem Dafoe. With Miyazaki now 82 years old, The Boy and the Heron has been widely billed as the director’s final feature. Fans are taking this with a pinch of salt – Miyazaki has reneged on public vows to retire several times before, dating all the way back to 1998. But if The Boy and the Heron (whose Japanese title translates to How Do You Live?) is indeed to be his goodbye, it’s a fittingly great one.

The impetus for the film started building in 2015, when Miyazaki created a short film for the Ghibli Museum in Tokyo, titled Boro the Caterpillar. The project involved working with Takeshi Honda, a younger animator whom Miyazaki took to and trusted. Wanting to work with Honda on a feature, Miyazaki began laying out ideas for The Boy and the Heron, bringing Honda in as animation director.

“Our producer [Ghibli stalwart Toshio Suzuki] was curious to know what would happen if we didn’t set a deadline and just left Miyazaki to do whatever he wanted,” Junichi Nishioka, the Vice President of Studio Ghibli, tells me. “For previous films, we had these production committees, film distribution companies, who would give us deadlines because they needed to book the theatres. With The Boy and the Heron, we stepped away from this committee structure. This was a totally independent film funded by Studio Ghibli.”

In fact, it was this need for independence that finally convinced Miyazaki to abandon his long-standing policy not to licence Ghibli films for streaming. In early 2020, the entire Ghibli catalogue began streaming on Netflix worldwide (except for the US, Canada, and Japan), in a deal that essentially bankrolled the production of The Boy and the Heron. The film ultimately ended up taking “three to four times” longer to create than Miyazaki’s previous projects.

Thanks in part to Miyazaki’s advancing age, he was forced to (slightly) pare back his duties, having exerted an exacting degree of control over his earlier directorial efforts. (“His concentration span is a little shorter than before,” Nishioka notes.) Throughout his career, Miyazaki was known for his meticulousness, and he would personally correct every frame of the film. With The Boy and the Heron, he was forced to place more trust in his collaborators.

Honda recalls a convivial and enjoyable working environment on The Boy and the Heron, with Miyazaki habitually wandering around the office and sharing anecdotes with his co-workers. “He would reminisce about working on [1979 TV animation] Anne of Green Gables with Isao Takahata,” recalls Honda. The early project was, he says, “very boring” to Miyazaki, because it involved animating tedious and mechanical motions – opening and closing doors, or making cups of tea. “That’s really all he could work on,” Honda says. “And he said, ‘This is not a man’s job.’ And he would also complain about Takahata-san, saying that he was such a sloth, and so lazy.” Nonetheless, it was Anne of Green Gables that led to the creation of Ghibli, and the decades-long collaboration between the two animation giants.

While his fastidious approach to animation has yielded some of the finest films of the last half-century, Miyazaki’s temperament and managerial style have also proved controversial, with both he and the late Takahata having reputations for being difficult to work with, and overly demanding on animators. The 2013 documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness offers a slightly sanitised but nonetheless insightful look at the inner workings of Ghibli, with Miyazaki coming across as a blunt, self-possessed and sometimes melancholic figure.

The word from his collaborators on TheBoy and the Heron seems to downplay this, however. “I was initially very much in awe of and intimidated by Miyazaki,” recalls Honda, “but he’s actually quite down to earth and very easy to work with.” Nishioka, meanwhile, describes Miyazaki as “sarcastic” and “charming but quite shy”, as well as “quite a contrarian”. He adds: “[Miyazaki] sometimes gets upset… he’s very human. He can’t really express when he’s happy… he could look cross, but he’s actually quite happy.”

A common criticism levelled against both Miyazaki and Takahata is that they failed to nurture younger talents properly: despite some of the best animators in Japan passing through the Ghibli infrastructure, there have been no clear heirs to the directorial throne. Some have shown more promise than others – such as Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who directed Arrietty and the superb When Marnie Was There, but who went on to found his own animation house, Studio Ponoc, in 2015. (He didn’t completely leave Ghibli behind, however, serving as a key animator on The Boy and the Heron.)

Another potential successor to Miyazaki is the director’s own son, Goro Miyazaki, whose own feature films, include Ghibli’s Tales from Earthsea, From Up on Poppy Hill, and last year’s Earwig and the Witch, a foray into 3D computer animation that proved deeply divisive among the Ghibli faithful. Responses to Goro’s work have been mixed, however, with Hayao Miyazaki making some infamously withering comments about his own progeny. "Shortly after I started making my first film, I had a huge fight with my father,” Goro later revealed. “For a long time we didn’t talk. He was opposed to the idea of me directing a film. He felt that it would be ridiculous for somebody with no experience to all of a sudden go into directing.” However, he noted that the arrival of his son – Miyazaki’s grandson – brought them together again.

It was this grandson that inspired Miyazaki to make The Boy and the Heron. Miyazaki’s previous “final film”, the unprecedentedly down to earth The Wind Rises, was widely interpreted as the director’s unflinching examination of his own career and legacy. The Boy and the Heron is, on the surface, a more fantastical affair, replete with anthropomorphic parakeets and sorcery – but is no less an exploration of Miyazaki’s own life.

It’s hard not to see Miyazaki himself in the figure of the Granduncle, an elderly, seemingly all-powerful, wizard (voiced by Mark Hamill in the dub) who created his own spectacular world – a world that has metastasised beyond his control. Part of the film’s drama comes from the Granduncle’s yearning for a successor, and Mahito’s reluctance or inability to become this. But while there are certainly echoes of Miyazaki’s own paternal relationship here, this was apparently not the intention. Rather, the Granduncle character was instead intended as a stand-in for Takahata, with Miyazaki imagining himself as the fledgling, self-sabotaging boy.

If The Boy and the Heron is to be the final rally of a cinematic institution, then it is a fitting one, a masterpiece on par with Miyazaki’s very best. But this is by no means necessarily the end, for Miyazaki – who is said to be already working on another idea – or Ghibli. The studio will outlive any one filmmaker, even one as monolithic as Miyazaki.

“It’s like Disney,” says Nishioka. “After Walt Disney passed away, the Disney company stopped making films for a while – but then they rejuvenated themselves. It’s the same with Ghibli: we’ve planted the seed so that maybe in the future, another generation can blossom in their own way.”

‘The Boy and the Heron’ is in cinemas now