‘It’s becoming like an airport’: How SpaceX normalised rocket launches

Just before Christmas in 2017, a SpaceX rocket flying over a California highway caused a multi-car pile up. Distracted drivers slowed down and stared up as a bright streak lit up the night sky, prompting reports on social media of meteors, UFOs and even Santa.

Today, drivers on the east coast of Florida barely glance as rockets taking off from Cape Canaveral soar overhead. “The first time I saw one I pulled the car over to the side of the road to watch it,” one Orlando taxi driver told me ahead of SpaceX’s latest launch. “Nowadays I look at it like I look at a plane. It’s just normal.”

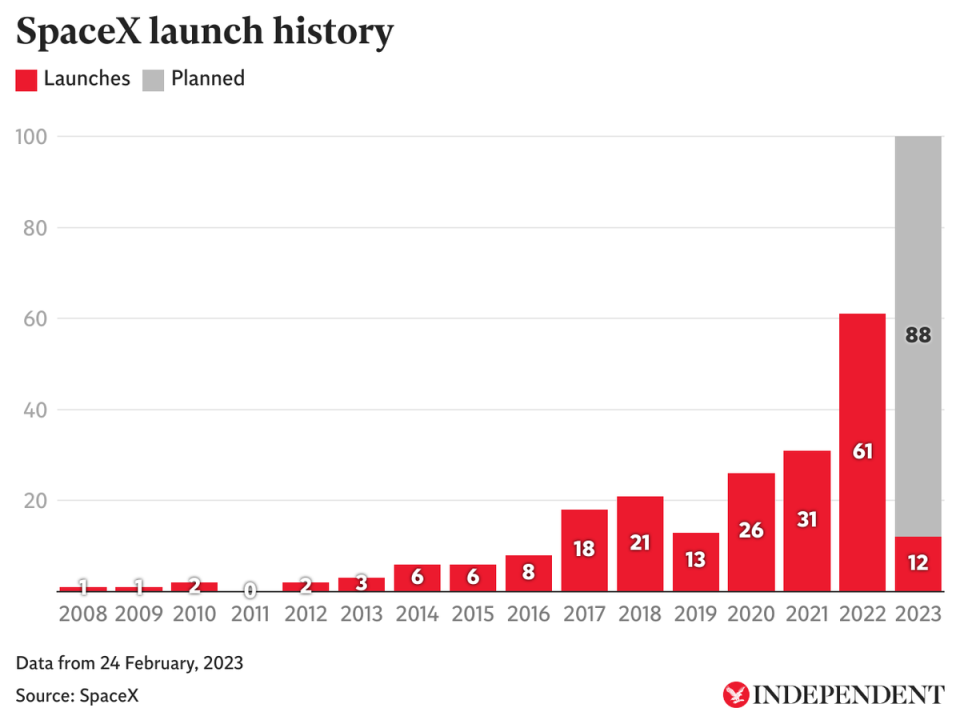

That launch last Friday was SpaceX’s 12th this year, and came less than nine hours after the previous one. Chief executive Elon Musk says he’s aiming for 100 launches in 2023, breaking the firm’s previous record of 61, set last year.

The 2022 tally represented more than a third of all rocket launches in the entire world, with all but one of SpaceX’s missions carried out by its Falcon 9 rocket.

It is this workhorse that has allowed SpaceX to transform access to space – cutting launch costs from hundreds of millions of dollars to just tens of millions, and offering everyone from governments to startups the ability to send payloads into orbit.

The key differentiator from its competition is its reusability, with some refurbished Falcon 9’s having now flown more than a dozen times.

Regular and reliable launches and landings mean there is no longer the anticipation or anxiety that came with early Falcon 9 missions, where malfunctions or explosions were a part of the development process. But with anything as complex as a rocket launch, complacency is the enemy of safety.

A SpaceX security guard, who has worked at the Cape Canaveral site for the last five years, told me that each mission requires renewed focus and discipline to make them seem so seamless.

“People get used to it but we can’t ever look at it as routine,” he said. “There’s too much at stake. In the case of the crewed missions, people’s lives are at risk.”

This waning public interest was no more evident than with the rapid progression of Nasa’s Apollo program. By the time Apollo 13 lifted off in 1970 – less than one year after the first ever Moon landing – public apathy had reached such a point that the launch was not even televised. It was only when the mission began to suffer difficulties that TV networks began to cover it.

It demonstrated how quickly something so extraordinary can seem entirely ordinary once novelty and risk is removed. In the 1940s and 1950s, newly opened airports would build large observation platforms for members of the public to come and watch the planes take off and land.

Nowadays, even the most diehard enthusiasts are becoming blasé about rocket launches.

“I don’t watch every launch at all anymore,” Tim Dodd, host of the Everyday Astronaut YouTube channel, said during a recent broadcast. “I’ll stream some of the really big ones, but back in the day I would wake up in the middle of the night to catch these launches, because there were maybe only five of them a year…

“[Now] there’s literally like two a week on average from SpaceX alone. It’s insane. It’s really hard to keep up with.”

SpaceX’s focus now turns to a crewed launch, having signed a $1.15 billion dollar contract with Nasa to deliver astronauts to the International Space Station. Planning to watch the Crew-6 launch is the SpaceX security guard, who asked not to be named. “I don’t think I’ll ever get bored of it,” he said. “At least not the noise.”

That noise is a crackling roar that makes your clothes rattle from two miles away. It is like a thousand fireworks firing off each second, and it is one of the reasons why spaceports will never be as ubiquitous as airports. Rockets typically require either a large body of water or a sparsely populated area to lift off over, while the best position for a launch site is near the equator to make the most of Earth’s rotational speed.

Despite the geographical limitations, some within the industry predict that there will be a point in the future where launches to orbit will exceed planes taking off on the surface of the Earth. Musk founded SpaceX in 2002 with the initial goal of making humanity a multi-planetary species. This ambition remains, and after 20 years it is beginning to be realised with the creation of SpaceX’s latest rocket: Starship.

Currently under development at SpaceX’s Starbase facility on the Gulf of Mexico, Starship is the biggest and most powerful rocket ever built. The first orbital flight test could take place as early as next month, and there will likely be huge interest as SpaceX attempts to push past another frontier on the path to Mars.

But when public interest surrounding Starship does inevitably begin to dwindle, the pace of progress is unlikely to slow down. Having pioneered the private space industry, SpaceX is now being joined by dozens of competitors that will not only increase the rate of rocket launches, but also continue to push down the costs.

The commercial opportunities mean that the new space race is no longer primarily funded by the taxpayer, and therefore does not depend on their interest and support.

For Didier Radola, an industry veteran of 30 years who was present at the latest launch, he is sure we will reach a point in the next couple of decades where crewed missions to Mars will become so mundane that people stop following them.

As the head of Moon programmes at Airbus, Radola says the rapid reusability of Falcon 9 and the ever-increasing launch cadence has seen SpaceX almost single-handedly revive the once moribund Cape Canaveral.

“It’s becoming like an airport with the amount of launches happening,” he says. “Long-term goals like setting up a base on the Moon and missions to Mars are now becoming concrete. Dreams are finally becoming affordable.”