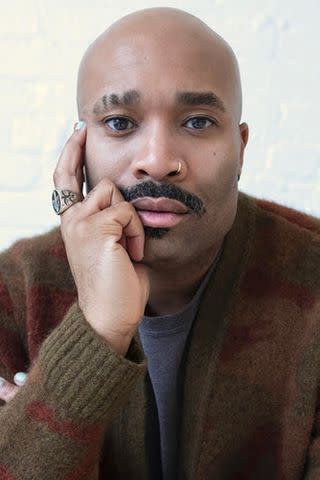

Author Joél Leon's New Essay Collection Seeks to Reveal: 'How Similar We All Actually Are' (Exclusive)

In an excerpt from 'Everything and Nothing At Once,' Leon explores what being Black means to him, and why "the totality of that experience is also hard to put into words."

Francisco Cole Cameron; Henry Holt and Company

Joél Leon and 'Everything and Nothing at Once'Author, performer and storyteller Joél Leon wrote his new book for those who are coming up after him, so young Black boys can feel seen.

Structured like an album, the essays in Everything and Nothing at Once: A Black Man's Reimagined Soundtrack for the Future (out June 4 from Henry Holt and Company) stand alone, like songs would. But taken all together, they're a cohesive journey from Leon's childhood in the Bronx, through parenting his own two daughters and into his self-understanding as a son, friend, partner, father and Black man in the world.

By turns lighthearted, touching, contemplative and fun and tackling topics as disparate as Leon's feeling about his growing belly to the challenges of co-parenting, the book contains multitudes, just like its subject matter.

"Growing up in the Bronx, I didn't see anyone who looked like me, was accessible and was willing to share their story," the author explains. "I wrote this book because I wanted young Black boys growing up, from the inner cities to the suburbs, to feel seen. And for the rest of America to see how similar we all actually are, no matter how varying our experiences may be."

Below, read an exclusive excerpt from an essay titled, What Kind of Black Are You.

Henry Holt and Company

'Everything and Nothing at Once' by Joél LeonI am both greeting and grieving myself. There are endings and beginnings. As a Black father to two Black girls, there is rarely if ever a moment when I am not fully aware of what that means within the context of the world we are living in today. There is almost always something at stake, something to live for and fight for. And isn’t that what manhood is supposed to be? If it is not hard or difficult then it must not be worth it. But I’ve decided for myself, for my girls, for my partner and family and friends and community, I want ease above all else. I want to make and leave room for a different way of being that doesn’t subscribe to the notion that our pain, suffering and trauma need to play a starring role in the stories of being. The greeting of myself is the reintroduction.

The PEOPLE Puzzler crossword is here! How quickly can you solve it? Play now!

Lauryn Hill talks about having to reintroduce herself to her parents. Because there was a shift, a transformation. And while doing so, there is also a dying. For in the rebirth, there is also a conclusion, a burying of what needs to die to allow something new to live. It feels at times that collectively we are at the intersections of both. I’ve found it most helpful to meet the expansiveness of the moment by expanding right along with it. We are achieving so much and yet, in parallel, are losing so much in the process.

Related: Best Books by Black Authors to Celebrate Black History Month

This time we’re in feels like a reflection point — an opportunity to sit with what was and has been, and the potential in what could be. In that potential, is love. Blackness is love, to me. To be loved is also very Black. And if we are looking at Blackness through that lens, then that love exists beyond a romantic sense of love and travels deeper into the vortex of humanity as a whole. Because to embody the fullness of Blackness and the spectrums of Black masculinity that exist within that framework, we get to reimagine what Blackness means with a new set of eyes and a new set of rules to play with.

Francisco Cole Cameron

Joél LeonI love being Black. Being Black is a birthright privilege, and a rite of passage, like learning how to parallel park or double Dutch. But just as much as I love being Black, I love being able to say I’m Black. The ability to speak, to use words, to use language, that ability to speak to a truth, to our ancestors — I’m in love with that, too. I am in love with language, with the languid and the lusty. With the length of a page and latitude of a levee breakage. It is this love of words and their use that has moved me to look at Blackness. Being Black is a noun and a verb. I learned this by looking in mirrors, staring at my reflection, standing naked and seeing Black skin, Black body — my Blackness staring back at me. I saw a thing, being.

Related: I Didn't See Empowering Examples for Black Boys in Pop Culture, So I Wrote One

And leaving my family’s two-bedroom apartment on Creston Avenue in the Bronx, going outside showed me what Black was also doing. Doing Blackness as a person living and breathing — dapping up elders, ducking into bodegas for bacon, egg and cheese sandwiches, reciting rap lyrics I learned from Video Music Box and snippets of the cassette tapes my big brother D would cop near the D train on Fordham Road in the Bronx.

Growing up, I learned that being Black is an all-encompassing everything — it is both whirlwind and movement, progress and processed hair; it is fistfights and chicken spots with “Fried Chicken” at the end of each title. It is liquor in barbershops and boyfriends in hair salons; it is long acrylics like Coko from the girl group SWV wore in her falsetto high notes during Showtime at the Apollo. Her stiletto heels set the benchmark for anything vocals-related in R&B videos during my formative 1990s years.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer , from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

These videos and the Blackness in them are what my younger self would watch and stare at, their Blackness and the volume in them staring right back. I’d be looking at all the caramel Black girls with the door knockers on, clutching their earlobes to the ends of the earth, weave tips reaching their waists. I say caramel because it was also here where I learned that light-skinned was preferable; that colorism was a pseudonym for “acceptable.” These are all constructs, binaries meant to be broken and laid out on the living room carpet for us all to bear witness to, a collective sigh of relief that the baggage of titles and labels can be eschewed for a higher sense of being and self we often aren’t afforded the luxury to have.

Early on, I learned that masculinity for a Black man is a tapestry of images pulled together from the media portrayals of what you were “supposed” to have — the exotic, light-skinned, curly-haired girl in haute clothes modeling for cameras; the car with the roof missing, money flying out of the windows, gold chains attached to bodies like tattoos. To be Black, to be a Black man in the era I grew up in, was easily everything and nothing at once. And to exist in that, to have that live both in you and on you, like a tattoo that is at once foreign and also embedded in you with the ink forever drying, is a hard thing to grapple with.

The totality of that experience is also hard to put into words. Much of my journey and purpose has been in translating my Blackness and my experiences surrounding Blackness, not for white eyes or the white gaze, but for Black folks who have struggled with having the language to describe how they view the world. The words and ways of expression I lacked then now show up in the prosaic language I use to illustrate those times now. This language is now more visual than anything else, and as I’ve gotten older, the language I have learned to use to express my Blackness has shifted. Blackness has shifted.

Excerpted from EVERYTHING AND NOTHING AT ONCE: A Black Man's Reimagined Soundtrack for the Future by Joél Leon. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2024 by Joél Leon. All rights reserved.

Everything and Nothing at Once: A Black Man's Reimagined Soundtrack for the Future is out June 4 from Henry Holt and Company and available for preorder now, wherever books are sold.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.