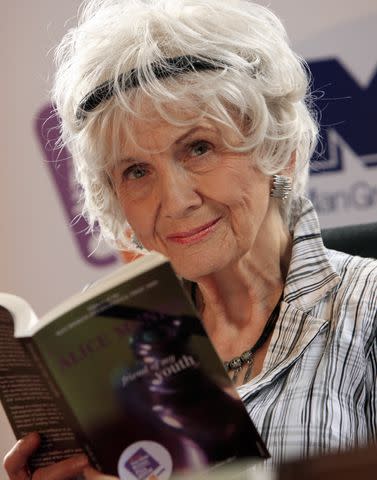

Author Alice Munro’s Daughter Reveals Stepfather’s Sexual Abuse, Mom’s 'Silence': 'She Was Erasing Me'

In a new essay, Andrea Robin Skinner recalls the abuse she suffered by her stepfather Gerald Fremlin, and claims her mother stood by his side

Chad Hipolito/The Canadian Press via AP, File; Steve Russell/Toronto Star via Getty Images

Alice Munro and her daughter Andrea Robin SkinnerAndrea Robin Skinner has revealed that her stepfather sexually assaulted and abused her as a child, and claimed that her mother, Nobel Prize-winning short story writer Alice Munro, remained by his side after learning of the abuse.

In an essay published by the Toronto Star on Sunday, July 7, Skinner says her stepfather, Gerald Fremlin, sexually assaulted her while she was visiting her mom’s Clinton, Ontario home in the summer of 1976, when she was just 9 years old, and continued to sexually abuse her for years.

Skinner also says that when her mother, who died in January at age 92, learned of his abuse, she remained with him — and even described him in the press “in very loving terms” — until he died in 2013.

Steve Russell/Toronto Star via Getty

Andrea Robin Skinner“When I was alone with Fremlin, he made lewd jokes, exposed himself during car rides, told me about the little girls in the neighborhood he liked, and described my mother’s sexual needs,” Skinner writes. “At the time, I didn’t know this was abuse. I thought I was doing a good job of preventing abuse by averting my eyes and ignoring his stories.”

After returning home from her summer in Ontario, Skinner told her stepbrother, Andrew, about the assault, and then her father, “who decided to say nothing to my mother.”

Two years later, Munro learned that Fremlin had “exposed himself” to another child, a 14-year-old girl, Skinner says, but he “denied it." When she asked about Skinner, Fremlin “reassured” her that the then-11-year-old was “not his type,” and Munro “said nothing,” she says.

As a teenager and young adult, her family’s silence continued, and Skinner says she suffered from bulimia, insomnia and migraines, which she attributes to the “private pain” she was experiencing as a result of Fremlin’s abuse. “By the time I was 25, I couldn’t picture a future for myself,” she writes.

Around the same time, Skinner told her mom what happened in a letter after hearing her empathize with a character who went through similar abuse in a short story. “As it turned out, in spite of her sympathy for a fictional character, my mother had no similar feelings for me,” she writes. “She reacted exactly as I had feared she would, as if she had learned of an infidelity.”

After Munro said was going to leave Fremlin, he made threats — he “told my mother he would kill me if I ever went to the police” — and wrote letters blaming Skinner and calling her a “homewrecker.”

The Nobel Prize winner stayed with him until he died in 2013, claiming she was informed about the abuse “too late” and “that our misogynistic culture was to blame if I expected her to deny her own needs, sacrifice for her children and make up for the failings of men,” Skinner says.

“I tried to forgive my mother and Fremlin and continued to visit them and the rest of my family,” Skinner writes. “We all went back to acting as if nothing had happened. It was what we did.”

PETER MUHLY/AFP via Getty

Alice MunroThen, 10 years later, after starting a family of her own and ceasing contact with Munro, Skinner read an interview in which the writer spoke glowingly about Fremlin, and decided to speak out about the abuse. “I had long felt inconsequential to my mother, but now she was erasing me,” she writes. “Now, I was claiming my right to a full life, taking the burden of abuse and handing it back to Fremlin.”

Skinner went to the police, and in 2005, Fremlin was charged with “indecently assaulting” Skinner in 1976. He was sentenced to two years of probation and ordered to avoid “any activity that brought him into contact with children under the age of 14 for two years,” she says.

“I was satisfied,” Skinner writes. “I hadn’t wanted to punish him. I believed he was too old to hurt anyone else. What I wanted was some record of the truth, some public proof that I hadn’t deserved what had happened to me.”

She was not, however, satisfied with the way the conviction impacted Munro. “My mother’s fame meant the silence continued,” Skinner writes. She remained estranged from her mom, as well as her entire “family of origin,” for nearly a decade.

Then, in 2014, after her siblings made an effort to “process their part in the silence around Fremlin’s abuse of me,” they reconnected. “As for my relationship with my mother, I never reconciled with her,” Skinner writes. “I made no demands on myself to mend things, or forgive her. I grieved the loss of her, and that was an important part of my healing.”

Munro’s Books, which was founded by the late writer, responded to Skinner’s essay in a statement. “Munro’s Books unequivocally supports Andrea Robin Skinner as she publicly shares her story of her sexual abuse as a child,” the statement reads. “Learning the details of Andrea’s experience has been heartbreaking for all of us here at Munro’s Books.”

Chad Hipolito/The Canadian Press via AP

Author Alice Munro"Along with so many readers and writers, we will need time to absorb this news and the impact it may have on the legacy of Alice Munro, whose work and ties to the store we have previously celebrated,” the statement continues. “It is important to respect Andrea’s choices over how her story is shared more widely. While the bookstore is inextricably linked with Jim and Alice Munro, we have been independently owned since 2014. As such, we are not able to speak on behalf of the Munro family. This story is Andrea’s to tell, and we will not be commenting further at this time.”

The Munro family — Andrea, Andrew, Jenny and Sheila — also provided a statement. “We would like to thank the owners and staff of Munro’s Books for being so supportive as Andrea shares her story of childhood sexual abuse, and journey of healing,” the statement reads.

"Alice and Jim Munro played significant roles in the store’s identity. By acknowledging and honoring Andrea’s truth, and being very clear about their wish to end the legacy of silence, the current store owners have become part of our family’s healing, and are modeling a truly positive response to disclosures like Andrea’s,” the statement continues. “We wholly support the owners and staff of Munro’s Books as they chart a new future, and respectfully request that they not be asked or expected to answer questions about the Munro family.”

If you suspect child abuse, call the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child or 1-800-422-4453, or go to www.childhelp.org. All calls are toll-free and confidential. The hotline is available 24/7 in more than 170 languages.

If you or someone you know has been a victim of sexual abuse, text "STRENGTH" to the Crisis Text Line at 741-741 to be connected to a certified crisis counselor.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.