Austin’s prostate cancer case spotlights broader silence around disease

Daniel R. Eagle, a retired Air Force general, is open about his prostate cancer. At least, he is now. Had he been in the military still, he said, he may have handled it differently.

“I certainly would have been a lot more circumspect,” said Eagle, who spent nearly 40 years in uniform, retiring in 2010. “I think I would have had more embarrassment about it, and been more hesitant to share with other folks. Because there is absolutely a stigma.”

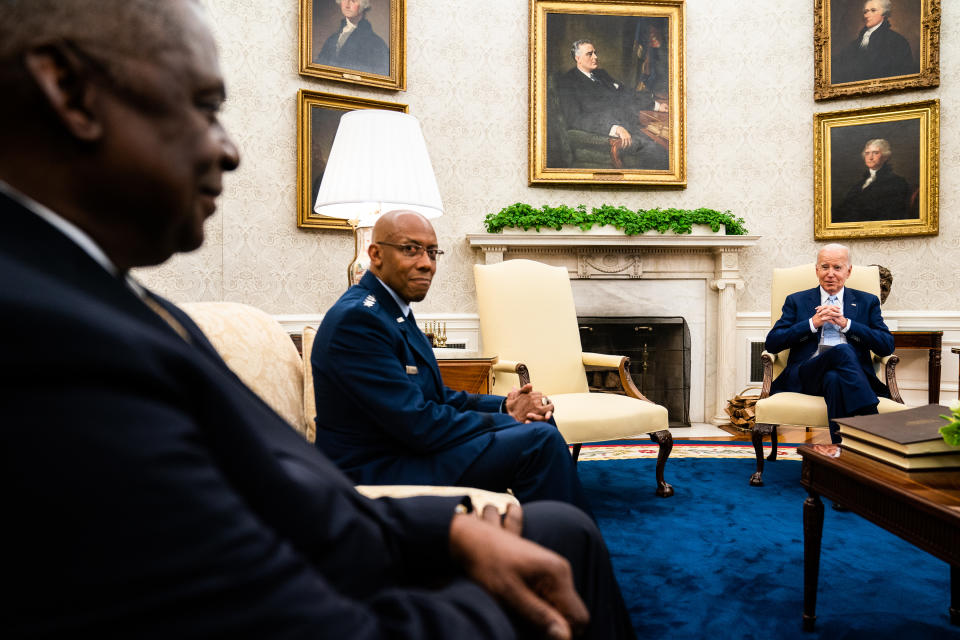

The military’s uneasy culture around cancer - and prostate cancer, in particular - spilled into public view earlier this month when the Pentagon disclosed that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, a retired Army general known to be intensely private, had secretly undergone surgery to treat the disease at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center on Dec. 22. Austin, 70, withheld the information from virtually everyone, including President Biden, and the diagnosis came to light only after he was hospitalized again Jan. 1 with serious complications from the procedure.

The ensuing firestorm - in which the White House, Pentagon and Congress all have promised to scrutinize how the commander in chief and Austin’s own No. 2, Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks, were left in the dark for so long - has clouded Austin’s tenure and raised questions about his judgment. He has acknowledged that he “could have done a better job” communicating, but in the weeks since has taken no questions about his decision-making, and declined even to recite prepared remarks - intended to glancingly address his condition - at the outset of a Jan. 23 virtual meeting of international leaders involved in Ukraine’s war effort.

The controversy has underscored a long-standing reluctance among men to discuss a disease that is highly treatable if caught early but often shrouded by awkwardness, said several military veterans who have been treated for prostate cancer. The institution’s penchant for toughness and stoicism often is to blame, they said, with some contending that Austin’s handling of the situation was a missed opportunity to normalize the broader discussion about this form of cancer.

Austin has been undergoing physical therapy for lingering leg pain and is expected to return to the Pentagon this week, said a senior defense official, speaking on the condition of anonymity because the issue remains sensitive. In a statement Friday, doctors John Maddox and Gregory Chesnut said the secretary had been seen again earlier in the day and has an “excellent” prognosis.

Some in the military who develop the disease choose to withhold the diagnosis from their colleagues out of concern for how it might affect their career or their unit, cancer survivors said. Others do so due to the intensely personal nature of a disease that attacks the male reproductive system, and treatment that can cause side effects such as incontinence and impotence.

“When you tell a guy he’s got prostate cancer, it’s a traumatic event,” said Michael “Bing” Crosby, a retired Navy fighter pilot who has survived three bouts with the disease. “It’s like an IED going off,” he said, referring to an improvised explosive.

About 1 in 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during their lives, according to the American Cancer Society, making it the most common form of cancer in men. African Americans have a higher rate, about 1 in 6, and some veterans also may have a higher propensity to develop the disease. A Defense Department study released last year found that pilots and aircrew, in particular, had higher rates of several diseases, including melanoma, thyroid cancer and prostate cancer.

Among those who have disclosed prostate cancer while serving in senior government positions are former secretary of state Colin Powell and Gen. David Petraeus. Powell, a retired Army general, had his prostate removed in 2003 and disclosed it soon after. Petraeus withheld his diagnosis for months while undergoing radiation treatment. He shared the news in October 2009 while serving as the head of U.S. Central Command and overseeing operations across the Middle East.

Robert J. Papp Jr., 70, who led the Coast Guard from 2010 to 2014, said he was unsurprised when he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2012. In screening, his score in a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test had been climbing for a couple of years. His doctor eventually suggested a biopsy and determined he had cancer.

One of Papp’s first steps, he recalled, was to schedule an appointment with his boss, Janet Napolitano, then the secretary of Homeland Security. He also notified Vice Adm. Sally Brice-O’Hara, the Coast Guard’s No. 2 officer at the time, to let her know that he’d be undergoing surgery and would need to turn over some duties to her while he recuperated.

“I can only speak for myself,” Papp said. “My experience throughout my career in the Coast Guard is that you always inform your seniors. Bad news does not get better with age. So, I think I’ve always had the intestinal fortitude to take stuff to my seniors, let them know what the problem was, and give them a solution, as well.”

Papp also issued a message to the more than 40,000 personnel under his command to inform them of his condition. When word reached the media, he said, the service confirmed he was undergoing treatment.

Papp said the way he handled the situation was informed by his experience years earlier when he developed alopecia, a medical condition in which patients can rapidly lose their hair. Papp, then in his 30s and the commander of a ship, said he took it hard as all of his hair fell out over about a six-month period.

“I looked completely different, and I was in a position that was front and center, in front of people every day,” Papp said. “I had to conduct business. I had to deal with the public. I don’t know, I guess it was just a sense of duty. I had to carry on with my responsibilities at the same time being embarrassed, feeling uncomfortable and having to deal with all that.”

Discussing his prostate cancer was easier for him after having endured that experience, he said.

Robert E. Milstead, a retired Marine Corps general, was diagnosed with an aggressive form of the disease early in 2012 and decided he would quickly need to inform his service’s top officer at the time, Gen. James F. Amos, and his peers.

“He needed to know that I had cancer, and it can be serious. And I had a pretty serious dose of it,” Milstead said. “Me personally, I think you have the responsibility to tell the guy you work for in our business. But it’s a very personal thing.”

Milstead, a helicopter pilot who’d gone on to hold senior jobs in the Marines, said prostate cancer had been looming for him, like “a lion outside the campfire,” after his grandfather and his father suffered bouts with it. Like Austin, he said, he developed a urinary tract infection after his prostate was removed, and later underwent radiation to make sure he’d conquered the disease.

Milstead, now 72, disclosed his diagnosis and treatment to the media in April 2012, and encouraged others to get screened. He said that, over the last decade, numerous service members, including generals, have approached him about their own conditions.

“There’s not a doubt in my mind,” Milstead said, “that I’ve saved a life by being open about it.”

Milstead called Austin’s handling of his own disease a “missed opportunity” to spread awareness. But it isn’t too late for him to do so, he added. “He can come out there and say, ‘In hindsight …’ And that’s a strength, to admit you screwed up.”

Eagle, 69, was a fighter pilot in the Air Force and served a stint as defense attaché in Moscow. He watched his PSA scores creep up as he embraced a second career teaching at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He relocated to California after retiring again, and in November 2022 was diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer.

Eagle underwent 28 radiation treatments at the Loma Linda University Medical Center in Murrieta, Calif., and has since resumed his active lifestyle that includes traveling, bicycling and hiking, he said. He agreed to sharing his story last year on the hospital’s website to help generate public awareness - a very different approach than what he saw in the military, he acknowledged.

“I recall going up the ranks, and people would talk about someone of a higher rank who had prostate cancer, and that was always hush-hush,” Eagle said. Men, he said, “need to come out from behind the curtains” and talk about their own diagnoses to destigmatize them.

Crosby, 63, said he was “very private” and “terrified, to be frank,” when he was diagnosed in 2015.

“I didn’t want it to get in the way of life,” he said. “I didn’t want it to get in the way of family.”

Crosby has beaten the disease three times and in 2016 founded Veterans Prostate Cancer Awareness, a nonprofit focused on education. Several studies have found that extended exposure to electronic components common in military life may be carcinogenic, he said.

Crosby said he hopes that Austin will step forward and discuss his experience. Candor from the Pentagon’s top leader could prompt more service members and veterans to get screened beginning at 40 years old, he said.

“He can say, ‘I’ve learned a lot through this journey, and I would love to share the lessons that I’ve learned,’” Crosby said. “There are positive things that come out of this.”

- - -

Razzan Nakhlawi contributed to this report.

Related Content

How Lions OC Ben Johnson became the hottest name this NFL hiring cycle

Kharkiv’s air defense struggles to halt nonstop Russian missiles