There’s another Christian movement that’s changing our politics. It has nothing to do with whiteness or nationalism

Just days before he would lead an unprecedented strike against the Big Three automakers, Shawn Fain, the president of the United Auto Workers, did something extraordinary.

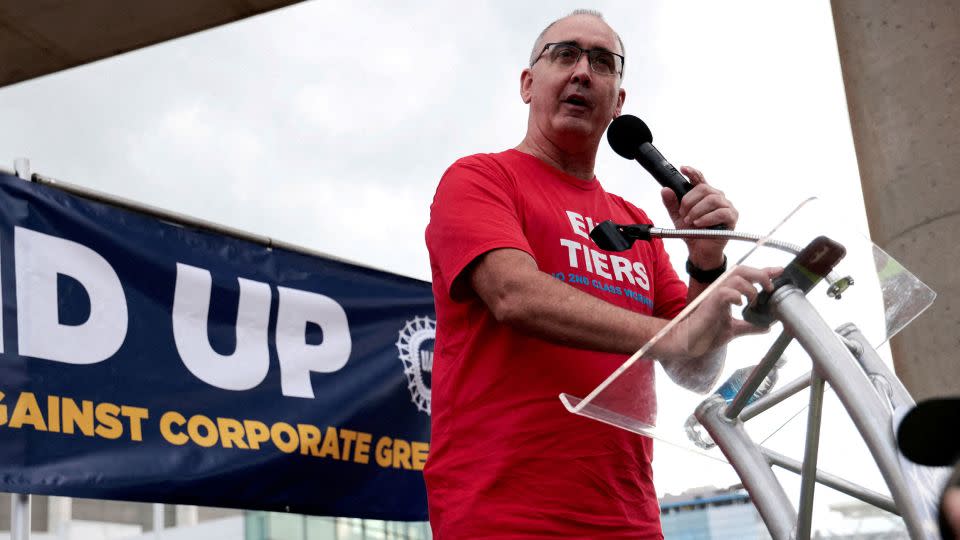

Fain, a middle-aged, bespectacled man who could pass for a high school science teacher, was warning auto workers they would probably have to strike, citing resistance by automaker CEOs whose companies he said made “a quarter of a trillion dollars” in profits while they “nickel and dime our members every day.”

He then paused before saying, “Now I’m going to get personal.”

Fain started talking about his Christian faith. He cited scripture, including Matthew 17:20–21, where Jesus told his disciples that if they have faith the size of a mustard seed they can move mountains because “nothing will be impossible for you.” He said that for UAW members, organizing and making bold demands of automakers was “an act of faith in each other.”

“Great acts of faith are seldom born out of calm calculation,” added Fain, who often carries his grandmother’s Bible. “It wasn’t logic that caused Moses to raise his staff on the bank of the Red Sea. It wasn’t common sense that caused Paul to abandon the law and embrace grace. And it wasn’t a confident committee that prayed in a small room in Jerusalem for Peter’s release from prison. It was a fearful, desperate, band of believers that were backed into a corner.”

Fain’s faith did move a corporate mountain — three, to be exact. After a six-week campaign of strikes, the UAW reached a historic agreement with General Motors, Ford Motor Company and Chrysler-owner Stellantis that would give workers their biggest pay raise in decades. The victory (it still has to be ratified by UAW members) not only reinvigorated an emboldened labor movement in the US, it also marked the revival of another movement in America: the Social Gospel.

Fain’s sermonette was remarkable because labor leaders don’t typically cite the Bible in such detail to justify a strike. But they once did. Fain’s decision to blend scripture with a strike is straight out of the Social Gospel playbook.

The Social Gospel was a Christian movement that emerged in late 19th-century America as a response to the obscene levels of inequality in a rapidly industrializing country. Its adherents took on the exploitation of workers and unethical business practices of robber barons like oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, who, when once asked by a reporter how much money he needed to finally have enough, purportedly said, “Just a bit more.”

The Social Gospel turned religion into a weapon for economic and political reform. Its message: saving people from slums was just as important as saving them from hell. At its peak, the movement’s leaders supported campaigns for eight-hour workdays, the breaking up of corporate monopolies and the abolition of child labor. They spoke from pulpits, lectured across the country and wrote best-selling books.

The popular trend of people wearing WWJD (What Would Jesus Do?) bracelets, for example, didn’t start off as Christian merchandizing. It was the slogan of a popular 1897 novel, “In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do,” written by the Rev. Charles Sheldon, a Social Gospel leader.

Fain’s sermonette underscores a trend that has largely gone unnoticed: The Social Gospel movement is making a comeback. Some may argue it never left.

When it comes to religion, stories about White Christian nationalism command most of the media’s attention today. But a collection of American intellectual and religious leaders are showing that there’s another type of Christianity that’s also shaping our politics, and it has nothing to do with Whiteness or nationalism.

These leaders include the UAW’s Fain, Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock, independent presidential candidate Cornel West, the Rev. William Barber II, the Rev. Liz Theoharis and the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Matthew Desmond. The most famous follower of the Social Gospel is the Rev. Martin Luther King, who was assassinated while helping lead a labor strike of sanitation workers.

All the above leaders are carrying on the torch of the Social Gospel in one way or another. They are using the Bible, as Social Gospel leaders once did, to argue in various ways that Christian deeds are more important than creeds and that unfettered capitalism “thrives on selfish impulses that Christian teaching condemns.”

It might sound like hyperbole to say that this resurgent form of the Social Gospel is changing our politics. But its proponents have helped reshape many Americans’ perspectives.

More Americans now believe that Big Tech monopolies are a growing threat to prosperity; more support a dramatic raise in the federal minimum wage; and more believe that government should help those least able to help themselves — whether it’s young people struggling with staggering student loans or the government sending money directly to families and small businesses impacted by the Covid pandemic. All these shifts in attitudes and policy reflect in part the influence of the Social Gospel.

Would Jesus go on strike?

Fain embodies this shift in thinking. He reached deep into the Social Gospel throughout the UAW strike, routinely deploying what one commentator called “strikingly Christian rhetoric.”

Christopher H. Evans, author of “The Social Gospel in American Religion: A History,” said he heard the Social Gospel in Fain’s UAW speeches.

“It sounds like there’s very much an emphasis on Jesus is for the worker, Jesus stands in solidarity with the laborers,” said Evans, a professor of the history of Christianity at Boston University. “That’s his consistent message and it runs through a lot of the tradition of the Social Gospel going back to the late 19th century.”

There was once a “deeply pro-labor vein of Christianity” in the late 19th and early 20th century that galvanized powerful working-class movements, wrote Heath W. Carter, author of “Union Made: Working People and the Rise of Social Christianity in Chicago,” in a recent essay.

“For countless workers throughout American history, traditional faith and labor militancy have gone hand in hand,” said Carter, an associate professor of American Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary. “From the labor movement’s earliest days, workers insisted that they organized because the Bible told them so.”

Union-friendly newspapers brimmed with scriptural quotations. The Gospel of Luke supplied some perennial favorites: ‘Woe unto you that are rich! For ye have received your consolation’ (6:24) and ‘the laborer is worthy of his hire’ (10:7).”

The modern-day Social Gospel prophets

Other current leaders carrying the Social Gospel torch have helped shape debates around everything from health care and minimum wage to attitudes toward the poor.

Sen. Warnock, for example, cites Matthew 25, where Jesus says people will be judged by what they do for “the least of these,” to argue for expanding Medicaid to recalcitrant states. In doing this, he is walking in the theological steps of the Social Gospel.

When the Rev. Barber, the founding director of the Yale Divinity School‘s Center for Public Theology and Public Policy, ties issues like climate change, immigration and voter suppression to his Christian faith, he is evoking the Social Gospel.

“The same forces demonizing immigrants are also attacking low-wage workers,” he said in an interview several years ago. “The same politicians denying living wages are also suppressing the vote; the same people who want less of us to vote are also denying the evidence of the climate crisis and refusing to act now; the same people who are willing to destroy the Earth are willing to deny tens of millions of Americans access to health care.”

But perhaps the most surprising place to find the Social Gospel is in the work of an Ivy League professor who is changing the way we look at poverty in America. Matthew Desmond is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City.” and “Poverty, by America.”

In his books Desmond argues that poverty is not the result of an individual’s moral failures but the result of a system in which “keeping some citizens poor serves the interests of many.” He also has said the US government has the resources to eliminate poverty.

“I want to end poverty, not reduce it,” he said in one interview. “I don’t want to treat it; I want to cure it.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Desmond is the son of a pastor. His books and interviews are filled with scriptural references that could be taken right out of a Social Gospel sermon from the late 19th century.

During another recent interview, Desmond said the moral outrage that’s characteristic of his work reflects his faith.

“I feel like often, throughout the Scriptures, when you see God getting really angry, it’s because some disadvantaged group is getting screwed,” he said. ”It’s like Isaiah 61:8 — ‘I, the Lord, hate robbery. I hate injustice. I love justice.’ This kind of righteous hate is something that I try to channel.”

How the Social Gospel differs from White Christian nationalism

If the Social Gospel was, and is, such a profound movement, why isn’t it better known today? And how does it differ from the most scrutinized form of Christianity in contemporary America: White Christian nationalism?

The second question is a tricky one, because it’s inaccurate to say that White evangelical Christians don’t have a tradition of social reform. In the 19th century, many White evangelical Christians fought for the abolition of slavery as well as women’s rights. Where many diverge from Social Gospel followers, however, is primarily in their attitudes toward poverty.

Many White evangelical Christians in the 19th century believed in a trickle-down spirituality — if individuals are saved, they will go on help the poor and transform society, said Evans, the Boston University professor. But the shocking explosion of poverty in cities of the Northeast US in the late 19th century made that belief seem inadequate.

“What do you do when you’re faced with the tenements filled with children dying of contagious diseases, where you have mass poverty?” Evans said. “The (Social Gospel) leaders were saying that capitalism as an economic system created these issues, that wealth was concentrated in the hands of a very small number and it’s not trickling down to serve the poor. There is no social safety net, and no regulation of factories and sweatshops.”

Perhaps the best distillation between a Social Gospel approach and a White evangelical approach can be heard in the wry observation of the Brazilian theologian Dom Helder Camara. He once said: “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.”

The future of the Social Gospel

For various reasons, the Social Gospel had gradually lost steam by the mid-20th century. The optimism embodied by its leaders seemed misplaced after the horrors of World War I. White evangelical culture grew in prominence. The mainline Protestant churches that carried, and still preach, its message began to lose members and influence.

But the prominence of people like Fain and other leaders who are carrying on the Social Gospel tradition prove that it remains relevant. They also exemplify a future where figures outside of traditional religious organizations — labor leaders, scholars, nontraditional pastors and other spiritual leaders — embody the Social Gospel message.

“There’s probably going to be a number of more movements like the United Auto Workers where people apply Christianity toward questions being raised about labor, wealth and capital,” Evans says. “It (The Social Gospel) won’t have the institutional muscle it had before, but you could still have these voices and followers.”

The climate in contemporary America seems ripe for the Social Gospel message. After decades of decline, major unions, including the Teamsters, the Writers Guild of America, the Screen Actors Guild, and others are flexing their muscle. Support for unions surged last year to its highest level since 1965. Inequality has soared to record highs. And a Pew survey last year found that a majority of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 had a negative view of capitalism.

It may be too much to expect the Social Gospel to return to its previous place of prominence. And the soaring optimism of old Social Gospel reformers may now seem as outdated as wobbly black-and-white silent films.

But what’s unsettling is that so many of the issues that early Social Gospel leaders battled are plaguing America again a century later. There a shocking concentration of wealth at the top, courts and corporations are crushing worker’s rights, and exploitive child labor — once seen as an appalling vestige of the past — has returned to parts of the US.

Fain’s UAW’s sermonette may have moved a mountain, but there are so many more that remain.

John Blake is the author of “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”

.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com