Analysis: Floyd death, protests show need for police reform

WASHINGTON (AP) — It looks like Washington has finally woken up.

The death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the nationwide demonstrations that followed have roused once reluctant lawmakers and even a president who preaches law and order to push now for police reforms.

The way Floyd, who was black, was pressed prone into the street, the way the white officer stared at the bystander's camera as he dug his knee into Floyd's neck while the man cried for his mother, for air, for his life, made for a moment that could not be ignored.

It drew together people of all races who poured into America's streets to express outrage and anger, and those demonstrations spread globally. And it led to a swift push for action from many lawmakers who rarely agree on anything.

“There are thousands of people marching in the streets, demanding meaningful change. People are demanding action,” said Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif. “We've seen enough. We've had enough commissions. We have studied these issues. We have convened opinion leaders. We have talked about these in private conversations and in public conversations. Now is time to act.”

Few changes of heart have come so quickly, especially in this highly polarized era in Washington. Lawmakers are pushing for legislation to change police procedures, President Donald Trump signed an executive order, and both sides are claiming the mantle of police reform.

Public opinion has shifted. About half of American adults now say police violence against the public is a “very” or “extremely” serious problem, up from about a third as recently as September 2019, according to a new poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

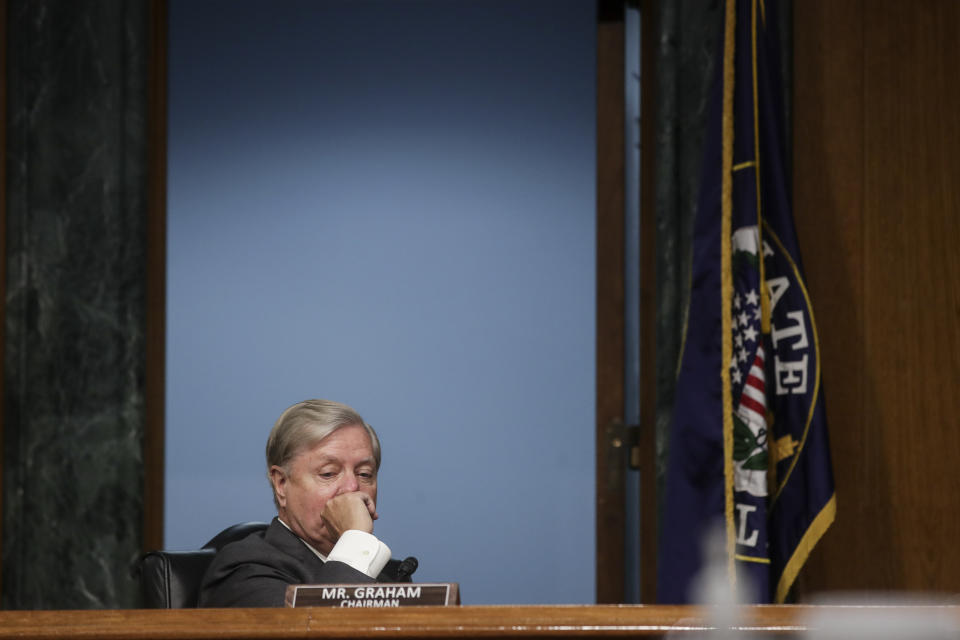

“Is policing in America a systematically racist enterprise? I’d like to think not,” Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on Tuesday. “Because I do believe most cops are far more good than bad. But when every black man in America believes that getting stopped by the cops is a traumatic experience, something happened.”

Graham talked about how he's rarely pulled over by police and when he is, “there is literally no fear.”

"I wouldn't like to live in a country where I'd be afraid to be stopped," Graham said.

Police reform has gone from an issue that fractured Congress to one where both parties speak in unison about the need for action. Both Democrats and Republicans have unveiled bills meant to bring major changes in how officers interact with communities, including accountability for misconduct and training on how to de-escalate tense situations. While Democrats have pushed for reforms before, the dueling bills seek core changes that would have been unheard of a few years ago.

Trump's executive order establishes a database that tracks police officers with excessive use-of-force complaints in their records. Many officers involved in fatal interactions have long complaint histories, including Derek Chauvin, the white Minneapolis police officer charged with murder in Floyd’s death. Those records are often not made public.

The executive order gives police departments a financial incentive to adopt best practices and encourage co-responder programs, in which social workers join police when they respond to nonviolent calls involving mental health, addiction and homelessness issues.

That idea has been percolating in communities of color and among activists for decades. And the proposed changes, banning chokeholds, for example, have already been made in many police departments. Some cities have pushed for de-escalation tactics, and others, like Camden, New Jersey, have dismantled departments and started over.

But there was something so visceral in the case of Floyd that it could not be ignored. It pushed law enforcement leaders nationwide to speak out publicly when they have kept silent before, and it forced lawmakers into introspection.

It also resurfaced other stories, from professional and working-class black men, of routine mistreatment at the hands of police. Even Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., talked about his experiences as a black man being stopped in the U.S. Capitol.

And then there are the deaths. Some aren't caught on video, like Ramarley Graham's in New York City. He was shot to death in his bathroom in 2012, not far from his little brother and grandmother. Or Freddie Gray's in Baltimore. He died in the back of a police van.

But some are captured on camera: Philando Castile's death in Minneapolis on livestream in 2016. Eric Garner's in New York. Laquan McDonald's in Chicago.

And 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, playing with a toy gun, was shot to death by a police officer in 2014.

These, too, have prompted protests. They gave birth to the Black Lives Matter movement. The Obama administration created a task force on police reform, and the Justice Department opened up nearly two dozen civil rights investigations into policing.

But there was a fractured Congress and lack of overwhelming public support. In 2012, Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill., was removed from the House floor after he wore a hoodie while calling for an investigation into the shooting death of Trayvon Martin.

Congress in 2015 and 2016 was instead focused on the Blue Lives Matter act, which would have made an attack on a police officer a hate crime. More than a dozen states passed similar laws after a spate of police killings. Congress passed a version of the law last year.

Then came Trump's election, and political and racial divisions became more fraught. Police reform was a decidedly lower Washington priority.

Until Floyd uttered the same words Garner did before he died: “I can't breathe.”

However late, police reform academics and activists are heartened by the push and the sudden coalescing around the issue.

“I am cautiously optimistic," said Durham, North Carolina, Police Chief Cerelyn Davis, the president of the National Order of Black Law Enforcement Executives. "That the cries of our America will be heard and acted upon so that once and for all black lives are valued in the eyes of the police, as more than a counterfeit 20-dollar bill, more than a carton of cigarettes, and more important than simply showing up at the wrong address.”

___

Colleen Long has covered criminal justice and policing issues for the AP since 2006.