He was an American war hero. Then he decided to smuggle arms to Israel.

One night last October in Tel Aviv, Danny Schwimmer hid with his family in an alley as rockets rained around them. They'd been out for a quick bite when the fighting broke out. "Just keep your head down," he told his daughter and his mother, Rina, who sat dazed in her wheelchair. "Now we got to wait." As he spoke, Israeli military jets streaked overhead, racing to counterattack against Hamas.

To the Schwimmers, the planes represented more than protection. Were it not for the late patriarch of their family — Danny's father, Al — there would be no Israeli Air Force, or perhaps even an Israel. As the country's founder and first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, once declared, "America's greatest gift to Israel was Al Schwimmer."

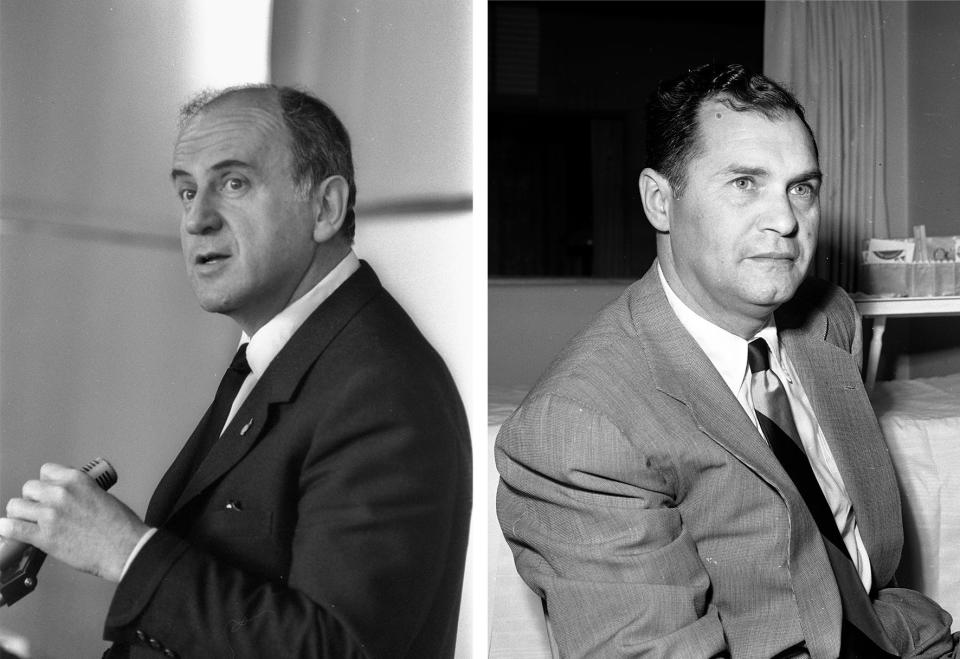

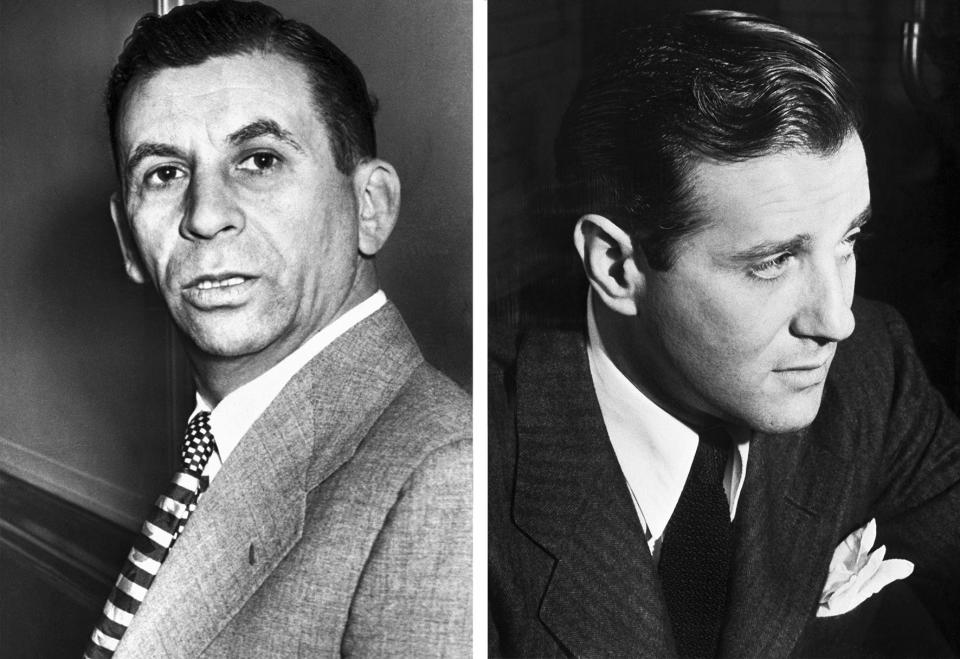

A decorated World War II veteran from Connecticut, Schwimmer was Israel's most notorious arms smuggler. In 1948, as Jews were fighting to carve a homeland for themselves out of Arab territory, he masterminded a covert, illegal, international operation that was equal parts "Argo" and "Mission Impossible." Working with the Jewish underground paramilitary, the Haganah, Schwimmer led a team of World War II veterans to break an American embargo and smuggle 125 military planes and more than 50,000 weapons to Palestine. They were supported in the campaign by a diverse and unlikely gang of volunteers, including Bugsy Siegel's publicist, the mobster Meyer Lansky, Pee-wee Herman's father, and Frank Sinatra.

"It was the beginning of the young nation," Sinatra later explained. "I wanted to help."

The aid made Schwimmer a hero in Israel — and an outlaw at home. "All the time the FBI was knocking on their door," Danny recalls. Convicted of violating the Neutrality Act, Schwimmer was stripped of his voting rights and his veterans benefits, becoming a second-class citizen in the nation he had gone to war to defend. So he immigrated to the country he had helped create, playing a pivotal role in building Israel's airline industry.

Schwimmer, who died in 2011, seldom discussed his story in public. But I was in a unique position to hear it firsthand. Thirty years ago I married into the Schwimmer family, and I spent many Thanksgivings talking to "Uncle Al." With wispy white hair and precocious eyes, he was wry, quiet, and extremely modest about what he'd done. He was also, as I later discovered, a man with plenty to hide, and a guilt that hounded him for decades.

In the years since his death, I've been talking to his son, Danny, and his widow, Rina, who provided me with access to his personal writings. Schwimmer's smuggling partner, Hank Greenspun, was especially eager to share the tale of his friend's exploits. On his deathbed in 1989, Greenspun asked his son, Brian, to let the world know what Schwimmer had accomplished on behalf of Israel.

"He was trying to make sure people knew what it took to birth a country and to help it grow," Brian recalls, "and what kind of people it took to do that."

One day in April 1947, Adolph "Al" Schwimmer visited Hotel Fourteen, home to New York City's hottest nightclub, the Copacabana. Still wearing his uniform as a TWA flight engineer, the 29-year-old had rushed to the hotel during a layover. But Schwimmer, who walked with a limp, hadn't come to enjoy the club. Instead he knocked, unannounced, on the door of an office listed in the hotel's business directory with two innocent words: Jaffa Oranges. It was the secret headquarters of the Haganah.

At the time, a crisis was mounting in the Middle East. The British were preparing to turn over control of Palestine to the United Nations, and hundreds of thousands of Holocaust refugees were attempting to resettle in the Holy Land. With the Arabs who lived there determined to defend themselves against what they saw as an invasion, war seemed inevitable. But Jews had few arms, let alone an organized military, and the United States had placed strict limits on arms exports. To circumvent the law, the Haganah had set up offices in Hotel Fourteen, working with American volunteers to smuggle arms to Palestine.

Schwimmer told me he felt a moral obligation to help. In the days after World War II, while he was working for TWA, his mother had asked him to find out what had happened to her parents and her siblings. Schwimmer journeyed to the family's village in Hungary, where he found a fresh monument in the Jewish cemetery. It listed the names of the many residents who had been murdered in Auschwitz, including his mother's entire family.

Schwimmer decided never to share what he had learned with his mother, out of a desire to protect her. "Don't tell ma," he later told Rina. "It'll break her." But he never forgot, and when he saw how Holocaust survivors were flocking to Palestine, he snapped into action. "Planes were needed," he recalled. "That's where I came in."

A self-described "quiet, puny teenager," Schwimmer had long dreamed of being a pilot. But after a football injury required part of his left leg to be amputated, he focused on building planes instead of flying them — starting with a rudimentary one he pieced together in his backyard in Connecticut. "All throughout my teen years I had to prove to myself and to others that I was strong, despite a damaged leg," he later recalled. After dropping out of high school to support his impoverished family, he went to work as a flight engineer. During the war he earned a medal for extinguishing an engine fire mid-flight. His friends took to calling him Wing Walker.

Now, with the war over, Schwimmer knew America had all the planes the Jews in Palestine would need — if he could get his hands on them. "Surplus planes were scattered in airport storages, depots, and literally strewn all over the Arizona desert, as far as the eye could see … rotting under the hot sun," as he put it. That's why he had showed up at the Haganah's office at Hotel Fourteen, after another veteran had given him the address. "I was the man they could count on to do everything possible to acquire the appropriate transport planes," he recalled. The prospect of working as a secret agent would also fulfill a boyhood fantasy spurred by a Sunday comic strip: "I was captivated by the image of Dick Tracy."

Joining the Haganah, Schwimmer discovered, wasn't as easy as just strolling through the door. Given the illegality of the operation and the need for secrecy, the underground group wasn't going to let some walk-in join its smuggling ring. They would check into Schwimmer, they told him, and let him know.

Soon after, a Haganah agent showed up at the family's home in Bridgeport and started asking questions. Schwimmer's mother, whose family had vanished in the Holocaust, was terrified. "His mother got very frightened," Rina recalled. "She told him her son was in the country. She was very, very antagonistic to this guy coming to check on her."

Once Schwimmer passed the background check, the Haganah sent him on a trial mission: to deliver sensitive files to agents in Rome. Using his job as a TWA flight engineer as cover, Schwimmer arranged for drop-offs during his layovers. After several successful runs, he was introduced to the new leader of the Haganah, Yehuda Arazi. Known as the "King of Ruses" for his chameleon-like disguises, Arazi had been in hiding since stealing thousands of rifles from the British. Together, the two men developed an outrageous plan. The US government, Schwimmer knew, was selling surplus planes from the war at drastically discounted rates. With money from the Haganah, he could buy the planes and recruit his old war buddies to smuggle them to the Jews in Palestine, circumventing the American ban on unlicensed arms exports.

Now all Schwimmer needed was a convincing cover. Armed with cash from the Haganah, he opened a hangar for a new commercial airline — Schwimmer Aviation — at the Lockheed Air Terminal in Burbank, California. Then, using the hangar as a hub for the operation, he purchased several surplus warplanes and flew them to Burbank.

To recruit pilots and mechanics to the cause, he reached out to his fellow veterans. Many refused to help. "They thought they'd slipped on their heads," recalled Danny, Schwimmer's son. "They'd just come back from World War II, and here they're going to go and risk their lives in a war on the other side of the world? Jews in the United States were not that enthusiastic to go die for the Jewish state."

But one by one, Schwimmer found vets who were willing to take the risk. Sam Lewis, the son of a Yiddish poet, had trained pilots in combat aerobatics during the war. His friend Leo Gardner was renowned as a flying ace. Milton "Milt" Rubenfeld, whose son Paul Reubens would later become better known as Pee-wee Herman, was a stunt-turned-fighter pilot. Like Schwimmer, Rubenfeld was modest about his involvement in the secret operation. "My father didn't like to talk about his many accomplishments," Reubens once said. But Rubenfeld, along with the others, joined on one condition. "Their only demand," Danny said, "was that their families be taken care of when they were away" — assuming they made it back at all.

But there was one crucial role remaining to be filled: a weapons expert. Schwimmer needed someone not only with a knowledge of munitions, but with the nerve to find and smuggle them to Palestine. One of the veterans who joined the group said he had just the guy. So Schwimmer flew to Las Vegas to recruit Hank Greenspun.

By the time Schwimmer showed up at his door, Greenspun was already embroiled in an organization as shadowy as the Haganah. For several years he had served as the publicist for the city's most notorious mobster, Bugsy Siegel. A fiery 38-year-old with a shock of dark hair and a Vegas tan, Greenspun shared roots that were remarkably similar to Schwimmer's: Both were raised by poor Jewish immigrants in Connecticut, shaped by the Holocaust, and decorated in World War II. After the war, Greenspun had put aside his law practice to pursue his passion for journalism, launching a weekly tabloid called The Vegas Life. His work had garnered the attention of Siegel, who hired him to promote the Flamingo, his new resort on the Strip. But now Siegel had been gunned down in what appeared to be a mob hit, and Greenspun was looking for a fresh start.

What Schwimmer had in mind was every bit as illegal as Siegel's operation. He explained his mission to Greenspun, who had specialized in munitions during the war. "I came straight to the point," recalled Schwimmer. "We needed his expertise." Working off a "hot tip" about a salvage yard in Hawaii that was thought to be sitting on more than 500 acres of airplane parts, engines, and weaponry — "the kind of stuff we really need" — Schwimmer asked Greenspun to enlist in the cause. "We want you to go there and check it out," he told him.

Greenspun shared Schwimmer's support of the Jewish people. But he had family — a wife and two kids — to consider. He told Schwimmer he was supposed to meet his wife that night at the Flamingo and take her to the opening of a radio station. Schwimmer told him he would have to call her from the road. Counting on Greenspun volunteering, he had already booked his flight to Hawaii.

The next day, Greenspun arrived in Oahu, where he met the owner of the salvage yard, Nathan Liff. The balding Jewish guy "looked like Santa Claus in a brightly patterned aloha shirt," as Greenspun wrote in his memoir, "Where I Stand." Liff, who spoke Yiddish, had also lost family in the Holocaust. The year before, his salvage yard had won a government contract to junk tons of surplus war munitions. Greenspun was amazed to see "hundreds of machine guns, ripped from the turrets of junked planes." He walked over to the nearest pile for a closer look. "There were thirty calibers and heavy fifties, water- and air-cooled jobs in profusion," he recalled. "I checked the action on the guns and found that they functioned almost as smoothly as new."

Liff, like Greenspun, was galvanized by the Holocaust. "He felt he had to do his part in creating a Jewish state, so this could never happen again," Schwimmer recalled. Rather than melt down the surplus weapons for scrap, Liff told Greenspun to take as much as he wanted — free of charge. "I didn't sell him nothing," Liff later recalled. "I gave it to him as a present. I knew what they needed it for, and they had no money. Today it's new, tomorrow it's junk. I'm in the junk business. I told them to take it away, to take what they needed."

At the junkyard, Greenspun used a forklift to load airplane parts into crates. But he knew that the Jews in Palestine would need even more munitions to defend themselves. As he worked, he noticed that there was an even larger supply of surplus guns and parts right next door, at the US Naval Yard. Though it was heavily protected, Greenspun figured out that every two hours, there was an eight-minute gap between the guards who patrolled the perimeter — just enough time for him to drive in a forklift and steal as many weapons as he could get his hands on. Working under the cover of night, he made off with 58 crates of weapons and parts. The plan was to ship them on a freighter to Schwimmer Aviation in California, and then on to Palestine.

Back in Burbank, Schwimmer and his smugglers were waiting. So was the FBI.

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations voted to divide Palestine between the Jews living there and the Arabs whose homeland it had been for centuries. That same month, the United States imposed a total embargo on shipping arms to Palestine. Come the following May, when the new state of Israel would declare its independence, the UN would pull out of the region — and a full-fledged war was sure to ensue. Without an air force, Israel was almost certain to lose. And the only shot at getting one was from Schwimmer and his fellow smugglers.

One day, as Schwimmer was working with his crew at Schwimmer Aviation, a clean-cut man in a dark suit approached him. Bernarr McFadden "Pat" Ptacek was one of the FBI's most notorious agents. Earlier that year, his investigations had helped provoke the signing of an executive order designed to root out communists supposedly lurking by the hundreds in the corridors of Washington. Now, Ptacek informed Schwimmer, he had a new target: rooting out Americans who were breaking the arms embargo on Palestine. The Feds didn't have enough proof yet to bust Schwimmer, but Ptacek assured him it was only a matter of time.

Schwimmer didn't take any chances. Shortly after the crates of munitions arrived from Oahu, he and his team hid them in a warehouse in Burbank. The next day, agents from the Customs Service stormed the docks looking for the weapons, and confiscated every crate that hadn't been secreted away. The close call left some of the veterans feeling conflicted. "It went against the grain to buck the same government we had fought to preserve only a few years before," Hank Greenspun recalled. But their loyalties were now divided — between the country they called home, and the one they saw as a new homeland for their people.

With the help of the Haganah, Schwimmer and Greenspun engineered a plan to ship the stolen weapons to Acapulco, where underground contacts would arrange to smuggle them to Palestine. Volunteers at the warehouse in Burbank — film producers, businessmen, lawyers, dentists — worked in shifts for a week, oiling and packing the guns. Unaware of the contents of the crates, a wealthy volunteer offered to transport them to Mexico aboard his 60-foot schooner, Idalia, for $3,000. But on the night the boat was loaded, when he realized what the crates contained, he raised his price to $17,000.

Greenspun refused to pay. "The Idalia is going all the way to Acapulco and it's taking the guns with it," he told the man. "You can bitch all you want, but that's the way it has to be." When the man asked what would happen if he refused, Greenspun pulled out his Mauser and pressed it to the man's temple. "I'll blow your brains out and heave you over the side," he said. The ship left California with the crates and Greenspun aboard.

Behind the scenes, the Haganah had been negotiating with the Mexican government to not only ship the arms to Palestine, but also to procure more weapons. Greenspun, armed with millions of dollars from the Haganah, served as chief purchasing agent. Operating out of a hotel in Mexico City, he spent months crisscrossing Central and South America, meeting with arms dealers and dictators, including Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic. "We inspected mountains of guns and acres of ammunition," Greenspun recalled, "prying up tarpaulins, spot-checking the firing mechanisms of rifles and machine guns, and testing the recoil tubes of cannons." Five percent of every purchase was paid to the Mexican authorities, in cash. When the Mexican government grew nervous about violating the US embargo on Palestine, Greenspun created a cover: He pretended they were shipping the arms to China. To forge the necessary documentation, he stole stationery from the Chinese Embassy in Mexico City.

Smuggling so many arms also required smuggling the huge sums of money needed to pay for them — as well as bribes. "My dad said they were always paying people off," Danny recalls. One day at the Hotel Fourteen, Schwimmer told me, the group needed to get a large sum to the port of New York, to pay the captain of a ship bound with their weapons to Israel. But the Haganah's representative in America, Teddy Kollek, knew FBI agents were lurking outside the hotel. So he pulled aside a young singer who was coming out of the Copacabana: Frank Sinatra. An early supporter of Israel, Sinatra listened to Kollek's predicament and agreed to deliver the money himself. "Despite Sinatra's reputation as connected with the Italian mafia," Schwimmer later wrote, "not a penny was missing from the bag." Kollek and Sinatra would go on to become lifelong friends.

At one point, Schwimmer himself served as a mule, heading to Mexico with $250,000 in a briefcase and a pistol tucked into his belt. The limping kid who had fantasized about being Dick Tracy was suddenly heading across the border with a fake passport and an alias, Erwin Johnson. But when Schwimmer arrived, he was pulled over by a Mexican police officer, who discovered his pistol. "A gringo isn't supposed to carry a gun in Mexico," the cop told him. Schwimmer was terrified. "I knew that if I ever entered the police station, I would never walk out of it alive," he recalled. "I wondered how they would dispose of my body." Instead, the cop asked him for a bribe of $20. Considering the fortune in Schwimmer's briefcase, it seemed like a bargain.

It was one thing to ship crates of weapons to Palestine — all it took was forged documents and plenty of money. But smuggling planes required a more elaborate ruse. And it started in a place few would suspect: Panama.

At the time, the Panamanian government was planning to launch a national airline for civilian flights. There was only one snag: The country didn't have any planes. Schwimmer realized if he could lease his surplus planes to Panama, he could fly them there legally and then take them on to Palestine. Under the guise of a fake company, Service Airways, he rented nearly a dozen planes to Panama to launch its national airline, known as LAPSA. "I was afraid that at any given moment the Panamanian government will catch on, and we'll all find ourselves in a jail cell," he recalled.

Before heading to Panama, Schwimmer met with a Haganah agent in New York who brought him a roll of microfilm, hidden in his underwear. It contained maps of makeshift landing strips hidden in some orange groves near Tel Aviv, where the planes could land, along with secret codes to use en route. Israel was "Oklahoma," the United States was "Detroit," and Panama was "Latin Detroit."

But at 3 in the morning, as the planes were preparing to depart, Schwimmer got a call. A federal official informed him that he had failed to receive approval from the State Department, which was required for all international flights. "They forbade us to fly," Schwimmer recalled. "I ignored the order. We had come too far to stop, an hour before our scheduled takeoff."

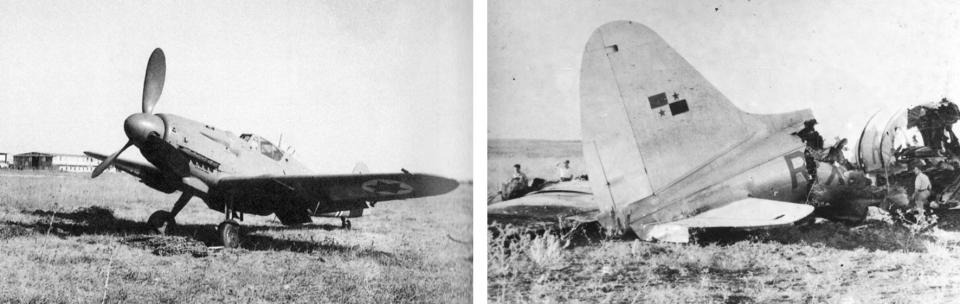

The planes from Burbank stopped in Mexico City to refuel before continuing on to Panama. They were packed with weapons — more cargo, it turned out, than they were designed to handle. As one of the planes ascended to 17,000 feet, the pilot, Bill Gerson, lost control. The plane plunged to the runway below, killing Gerson and his mechanic, Bud King. They were both veterans of World War II who believed in Schwimmer's cause — and they were the first to die for it. They wouldn't be the last.

A half-century later, Schwimmer was still haunted by the crash. He couldn't forget how, when he met with Gerson's wife, she had slapped him and called him a murderer. "He was heartbroken," Rina told me. "He felt for many years that it was his fault. He overloaded the airplanes, because Ben-Gurion was screaming, 'We don't have bullets for our guns! We need ammunition immediately!'" Schwimmer took responsibility for overloading the plane. "It was overweight, and I am to blame," he told Greenspun and his team. "But we have to do this. This is necessary."

On May 6, 1948, just eight days before Israel declared independence, Panamanian officials, military leaders, and celebrities gathered at the airport to witness the arrival of planes the press had dubbed "the pride of Panama." "Everybody from the Panamanian government with wives and children came to see this miracle," Rina recalled. Schwimmer's planes, now bearing the LAPSA logo and Panamanian registration numbers, eased down the tarmac as a brass band played. "It's a new era for the people of Panama," the pilot Sam Lewis told the crowd. A group of tourists and officials, armed with several crates of Pepsi, were taken on a demonstration flight. Then Lewis and the other pilots took off, flying away in a long procession until they disappeared into the horizon. Unbeknownst to Panama, its new national airline was on its way to Israel.

"They took off during the parade," said Danny Schwimmer, "and they never came back."

With the war in Israel fast approaching, the smuggled planes made their way toward Tel Aviv. Schwimmer and his team had arranged for refueling stops along the way. From Panama, the planes flew to Suriname, then on through Brazil and Senegal, before landing in Casablanca. There, the pilots encountered a crowd of protesters, raging over Israel's coming independence and chanting "Kill the Jews!"

The next stop was Catania, Sicily, where the Mafia had arranged for refueling through a man sympathetic to the cause: the gangster Meyer Lansky. Lansky, who had been partners with Greenspun's former boss, Bugsy Siegel, was a staunch Zionist who had been funneling money and arms to the Haganah. But when members of Schwimmer's team landed in Sicily, the local mobsters hadn't gotten the word and angrily confronted the Americans. The shaken pilots, unable to converse in Italian, uttered two words: "Meyer Lansky." They spent the rest of their time in Sicily enjoying the local cuisine, and departed with a gift: a crateful of Tommy guns.

The American planes weren't the only ones Schwimmer and his team smuggled into Israel. Ben-Gurion, as Schwimmer later recalled, had received a coded message from Europe. Czechoslovakia was also willing to sell arms to Israel, both for the money and as a statement of support. And the Czechs had just the thing to help the Jews fight for independence: surplus Nazi warplanes. A Czech Holocaust survivor provided Schwimmer's team with 25 Messerschmitts left over from the war. There was just one problem: the giant swastikas painted on the tails of some of the planes. So the Americans scrounged up some buckets of white paint. "The swastika was removed, and replaced with the Star of David," Schwimmer recalled. "The irony of it — German Messerschmitts, produced in Czechoslovakia, flown by American Jewish pilots fighting for the creation and protection of the Jewish state."

Joined by the planes from Burbank, the Messerschmitt pilots headed for a secret airfield hidden in the orange groves north of Tel Aviv, with a landing strip "lit by tin cans filled with sand and burning oil," as Schwimmer recalled. "Everything else was just as primitive, including the single shabby hangar." The conditions proved deadly: One of the Czech planes crash-landed, killing the navigator. But one by one, the other planes landed safely. Schwimmer had pulled off a seemingly impossible heist: stealing planes and arms that had belonged to both the Nazis and the Americans, and delivering them to Israel. With a single stroke, he had given the Jewish state its very own air force.

Israel quickly deployed the planes in battle. The first air attack succeeded in halting the Egyptian advance on Tel Aviv. During the second attack, the fighter pilot Milt Rubenfeld was met with enemy gunfire over Egypt, and had to parachute out of his plane near a remote village. Because the Jewish locals didn't know their fledgling country had an air force, they readied to shoot Rubenfeld, assuming him to be an enemy pilot. He saved himself by shouting the only words of Hebrew he knew. "Gefilte fish!" he yelled. "Shabbos!"

More planes followed, including B-17 bombers that Schwimmer had acquired back in the States. Schwimmer was aboard one of the bombers, en route to Tel Aviv, when he received an urgent message from the Israeli military command. The Egyptians were advancing, and Israeli troops desperately needed air support. Schwimmer would have to drop the first bombs himself, as his plane flew over Cairo. The only way to do that was to manually open the hatch and roll out the bombs by hand.

Fifty years later, at a Thanksgiving dinner in Connecticut, Schwimmer told me he recalled the plane flying so low that he could see an enemy soldier sitting in an outhouse. When I asked him how he felt at that moment, he paused. There wasn't time for feelings, he explained. "It was war," he said. "They would have killed us too, if they could."

On March 10, 1949, Israel won the war. Schwimmer's aid proved to be pivotal to the victory. "Without Al's operation, Israel would have never survived its first war," said Boaz Dvir, a professor at Pennsylvania State University who's the author of "Saving Israel," an account of Schwimmer's mission.

But the end of the war didn't end Schwimmer's battles. That October, Schwimmer and others in his group, including Hank Greenspun, were put on trial in Los Angeles for violating the Neutrality Act. They faced tens of thousands of dollars in fines and years in federal prison.

Ben-Gurion ensured the men had the best lawyers to defend them. Schwimmer pleaded not guilty. His defense was what he saw as the justness of his cause. "We did not deny the fact that we smuggled planes and military equipment, as charged," he insisted. "We did nothing to endanger American security. All we did was protect a friendly nation from hostile surrounding armies."

The attorney for the arms smugglers pointed out that the men on trial were American heroes who had served their country during World War II. Some, like Schwimmer, had lost family in the Holocaust. When a prosecutor suggested that one of the non-Jews on trial, Charlie Winters, had sold the group B-17s just to make a quick buck, Winters said his support had nothing to do with money. "I am Irish, and I hate the British," he said, referring to what he saw as England's abandonment of Israel. "I am aware of where my B-17 were destined for."

Winters was found guilty and received 18 months in prison. Schwimmer and Greenspun, along with others involved in the operation, were convicted and fined $10,000, but weren't sentenced to prison. Schwimmer felt "appalled" by the verdict. "Justice and the law," he said, "aren't always on the same page."

In the eyes of the law, and of many who opposed the creation of Israel, Schwimmer and his crew were nothing but criminals — convicted arms smugglers who stole government property, violated an American embargo, and illegally took sides in a foreign conflict. But history has a way of switching sides. As the years passed and Israel became one of America's closest allies, what was once viewed as treasonous came to be seen as an act of heroism. Greenspun, who later took on Joseph McCarthy as publisher of the Las Vegas Sun, was pardoned by President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Despite his bravado, it meant a lot to him to be restored to his full rights as an American citizen.

"My dad was a World War II hero," Brian Greenspun, who succeeded his father as publisher of the Sun, told me. "So it was kind of incongruous that he would do all this for his country, and yet he couldn't vote in his country. I'm sure it bothered him inside."

After his conviction, Schwimmer was invited by Ben-Gurion to move to Israel and create the country's aerospace industry. He founded Israel Aerospace Industries, which manufactured aircraft for military and civilian use, and served as its first president. Today IAI is a state-owned company with 14,000 employees. The battered old planes Schwimmer provided to help Israel secure its independence have been replaced by fighter jets, missiles, and drones built by the company he founded. Today they're providing Israel with air superiority in a different war — this time in Gaza.

Over the years, Schwimmer also remained active as an arms smuggler, helping to move American weapons during the Iran-Contra affair. Yet he refrained from seeking a pardon from the United States, where he continued to be deprived of his voting rights. As he told me many times, he felt he had done nothing that required pardoning. "He didn't think he did anything wrong by helping the state of Israel," Danny said. In the end, Schwimmer didn't have to ask. In 2001, at the urging of Brian Greenspun, Schwimmer received a presidential pardon from Bill Clinton.

"It was the first and only time I saw Al Schwimmer cry — this guy who was always tough as nails," Brian told me. "It meant something to him. He was a full American again."

David Kushner is a regular contributor to Business Insider. His new book is "Easy to Learn, Difficult to Master: Pong, Atari, and the Dawn of the Video Game."

Read the original article on Business Insider