Accusing Advocates of Profiting From Racial Conflict Is Nothing New—And It's Always Been Problematic

Crowds gather at the National Mall during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom political rally in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 28, 1963 Credit - NBCUniversal via Getty Images

In September, Boston University announced that it was launching an inquiry into the finances of its Center for Antiracist Research. Founded in 2020 by Ibram X. Kendi, a prominent author and anti-racism advocate, the Center’s self-professed commitment to “solving the seemingly intractable problems of racial inequity and injustice” garnered $45 million in donations and pledges during its first year. However, the Center’s widely documented recent troubles, including staff layoffs and criticism of Kendi’s leadership by former employees, sparked considerable backlash.

At the beginning of November, Boston University announced that its initial audit found “no issues with how [the Center] managed its finances.” And yet, conservative media remains fixated on denigrating Kendi as part of “a new generation of race hustlers” eager to capitalize on racial discontent.

Both ubiquitous and ill-defined, the specter of the “race hustler” looms large over contemporary racial politics in the United States. Accusations of “race hustling” underpin the broader right-wing effort to delegitimize Black activism and demands for social and racial justice, and the term has been applied to figures ranging from football player Colin Kaepernick to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The “race hustler” term has commonalities with the “race baiter,” another familiar label levied against individuals accused of “exploiting” racial conflicts. But while the alleged motivations of the “race baiter” vary—from a supposedly misplaced sense of personal grievance to the advancement of specific political agendas—the primary critique of the “race hustler” is personal financial enrichment.

It's tempting to read the “race hustler” as a recent phenomenon spawned by partisan politics, the advent of cable news and the internet age, and white backlash to a revival of Black activism in recent years. However, the term and its antecedents have a long history that highlights the complex intersections of Black politics, racial protest, and media culture—as well as the intensity with which Black spokespeople, along with their supporters and adversaries, have struggled to define the boundaries of “legitimate” race leadership.

Read More: Ibram X. Kendi: ‘Racist’ Is an Adjective, Not a Noun. Understanding Why Is Important

Over a century ago, Black leaders were often the ones to drive efforts to denounce African Americans who sought to “make a racket out of race.” In his 1901 treatise Up From Slavery, racial accommodationist Booker T. Washington took aim at Black spokesmen who “make a business of keeping the troubles, the wrongs, and the hardships of the Negro race before the public.” Washington’s remarks were directed towards progressive Black activists such as W.E.B Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter.

In response, Du Bois, Trotter, and others described Washington as a “fraud” and his advocacy of accommodationism as a “dangerous half-truth.” At the core of such accusations were ideological disagreements over how to best advance the interests of Black people among a new generation of Black civil rights leaders. Washington prioritized a program of vocational education and economic self-reliance by working within white power structures. By contrast, Du Bois and others advocated for “civil rights agitation,” directly challenging Black disenfranchisement and the legal and political infrastructure of Jim Crow.

These differences were amplified by American print culture and an ascendant Black press, which had been revolutionized by technological advances and the growing affordability of newsprint production during the last two decades of the 19th century. Such public conflict was often by design. Washington utilized his extensive media connections to propagate what Susan Carle describes as “vicious and untrue rumor campaigns” against his ideological adversaries. Similarly, Trotter and Du Bois were prolific journalists who used publications such as the Boston Guardian and The Crisis to issue broadsides against Black leaders whom they believed to be guilty of “fraud and humbug.”

Read More: The Perils and Promise of America's Third Reconstruction

In the end, such rhetoric brought meaningful ideological disagreements into the public eye, but also threatened to distract from the shared goal of Black equality. At the same time, it demonstrated the media’s power to shape the public reputations of individual Black spokespeople and civil rights organizations.

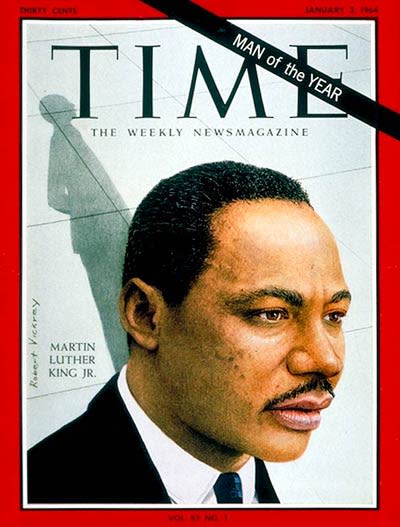

The consequences of these dynamics became evident by the second half of the 20th century as discussions of the “race racketeer” or “race hustler,” informed once again by powerful new media technologies, shifted into mainstream media discourse. By the March on Washington in 1963, more than nine in ten American households were watching the civil rights struggle unfold on television sets in their living rooms. Network television helped to raise awareness of new civil rights organizations and make Black spokesmen such as Martin Luther King Jr. national celebrities.

Yet this expanding national media also provided space for Southern politicians, white supremacists, and other movement critics to repeatedly attack civil rights leaders and organizations as “outside agitators,” “demagogues,” and self-serving opportunists. When TIME selected King as the 1963 “Man of the Year,” it printed responses from readers including Cleveland resident Ted Kurlow, who declared his astonishment “that a race racketeer should become Man of the Year.”

Growing factionalization within the Black freedom struggle during the second half of the 1960s also emboldened such critiques, with Black moderates such as psychologist Kenneth Clarke denouncing Black Power advocates as “racial racketeers who sell themselves to the highest bidder.” Whereas such intraracial accusations were framed by specific strategic and political differences, white racial conservatives capitalized to characterize the entire movement as illegitimate and a “hustle.” Similarly, network television and white-owned newspapers platformed critics who attacked Black Power radicals and Black mayoral candidates alike as “racial racketeers…who constantly fan racial misunderstanding and discord” for financial gain.

In recent decades, the language of the “race racketeer” has been eclipsed by that of the “race hustler.” Conservative politicians and media commentators have been the driving force behind this rhetorical shift, with much of their ire directed against a new generation of Black spokesmen—the “Black public intellectual”—who became a fixture of the nation’s developing cable news ecosystem during the 1990s. Black economist Thomas Sowell and Black Republican J. C. Watts led the charge, with their criticisms of “race hustling poverty pimps” widely circulated by right-wing media.

Such complaints demonstrated how, by the Bill Clinton era, the language of the “race hustler” had expanded beyond Black civil rights activists to include an interracial group ranging from “diversity consultants” to politicians and Ivy League academics. They also highlighted conservative anxieties over the role of new media forms in advancing progressive agendas, and a parallel awareness of how these same media forms could be used to undermine the struggle for racial equality. Against the charged backdrop of America’s developing “culture wars,” the language of the “race hustler” was well suited to an increasingly partisan media and political ecosystem.

Viewed against this backdrop, the confluence of elevated racial tensions, a revival of Black activism, and the role of social media in facilitating both over the past decade can be linked to the latest revival of the “race hustler” in public discourse.

Of course, for many conservative commentators, the perception of financial misconduct appears to be more important than actual evidence. Kendi’s Center for Antiracist Research is a useful case study. Whereas figures such as Princeton professor Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor have raised nuanced questions about the limits of Kendi’s antiracist agenda and the complex relationship between racial protest, academia, and nonprofit organizations, it’s doubtful whether Boston University’s initial inquiry will do much to dissuade right-wing commentators from describing the Center as anything other than a “multi-million-dollar grift.”

From this perspective, anyone who positions themselves as a leader for racial justice (or, in some instances, simply talks about race at all), is at risk of being branded a “race hustler.” Indeed, the continued specter of the “race hustler” is a reminder that the “legitimacy” of Black activists and organizations has always been highly contested.

Writing in 1959, historian Richard Bardolph noted that any given Black spokesman could be “a militant race hero” to one person, but a “cheap race hustler” to another. Throughout American history, the struggle for Black equality has taken many forms, and has rarely been a binary between “sincere race leaders” and illegitimate “race hustlers.” Every movement has its profiteers, and no activist or organization fighting for Black rights is beyond reproach. Nevertheless, the willingness of those on the right to brandish the term so uncritically is not unique to this moment—but rather demonstrates the lasting power of using such language to try and undermine the broader struggle for racial justice.

James West is a Lecturer in Arts and Sciences at University College London and Co-Director of the Black Press Research Collective, based at Johns Hopkins University. Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here.

Write to Made by History at madebyhistory@time.com.