Modern grapes exist because the dinosaurs died out, new research finds

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Grapes have been intertwined with the story of humanity for millennia, providing the basis for wines produced by our ancestors thousands of years ago — but that may not have been the case if dinosaurs hadn’t disappeared from the planet, according to new research.

When an asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago, it wiped out the massive, lumbering animals and set the stage for other creatures and plants to thrive in the aftermath.

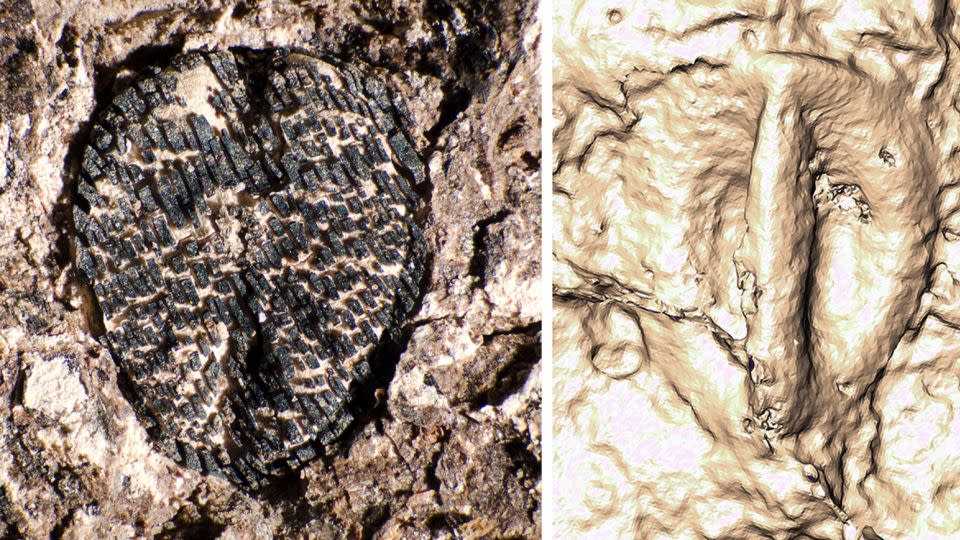

Now, the discovery of fossilized grape seeds in Colombia, Panama and Peru that range from 19 million to 60 million years old is shedding light on how these humble fruits captured a foothold in Earth’s dense forests and eventually established a global presence. One of the newly discovered seeds is the oldest example of plants from the grape family to be found in the Western Hemisphere, according to a study on the specimens published Monday in the journal Nature Plants.

“These are the oldest grapes ever found in this part of the world, and they’re a few million years younger than the oldest ones ever found on the other side of the planet,” said lead study author Fabiany Herrera, an assistant curator of paleobotany at the Field Museum in Chicago’s Negaunee Integrative Research Center, in a statement. “This discovery is important because it shows that after the extinction of the dinosaurs, grapes really started to spread across the world.”

Much like the soft tissues of animals, actual fruits don’t preserve well in the fossil record. But seeds, which are more likely to fossilize, can help scientists understand what plants were present at different stages in Earth’s history as they reconstruct the tree of life and establish origin stories.

The oldest grape seed fossils found so far were unearthed in India and date back 66 million years, to about the time of the dinosaurs’ demise.

“We always think about the animals, the dinosaurs, because they were the biggest things to be affected, but the extinction event had a huge impact on plants too,” Herrera said. “The forest reset itself in a way that changed the composition of the plants.”

A difficult search

Herrera’s PhD advisor, Steven Manchester, who is also a senior author on the new study, published a paper about the grape fossils found in India. It inspired Herrera to question where other grape seed fossils might exist, like South America, although they had never been found there.

“Grapes have an extensive fossil record that starts about 50 million years ago, so I wanted to discover one in South America, but it was like looking for a needle in a haystack,” Herrera said. “I’ve been looking for the oldest grape in the Western Hemisphere since I was an undergrad student.”

Herrera and study coauthor Mónica Carvalho, assistant curator at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology, were doing fieldwork in the Colombian Andes in 2022 when Carvalho spotted a fossil. It turned out to be a 60 million-year-old grape seed fossil trapped in rock, among the oldest in the world and the first to be found in South America.

“She looked at me and said, ‘Fabiany, a grape!’ And then I looked at it, I was like, ‘Oh my God.’ It was so exciting,” Herrera said.

Although the fossil was tiny, its shape, size and other features helped the duo identify it as a grape seed. And once they were back in the lab, the researchers carried out CT scans to study its internal structure and confirm their findings.

They named the newly discovered species Lithouva susmanii, or “Susman’s stone grape,” in honor of Arthur T. Susman, who has been a supporter of South American paleobotany at the Field Museum.

“This new species is also important because it supports a South American origin of the group in which the common grape vine Vitis evolved,” said study coauthor Gregory Stull of the National Museum of Natural History.

The rocks had been deposited in ancient lakes, rivers and coastal settings, Herrera said.

“To look for such tiny seeds, I split every piece of rock available in the field,” he said, adding that the difficult search “is the fun part of my job as a paleobotanist.”

Encouraged by their find, the team conducted more fieldwork across South and Central America and found nine new species of fossil grape seeds trapped within sedimentary rocks. And by tracing the lineage of the ancient seeds to their modern grape counterparts, the team realized something had enabled the plants to thrive and spread.

How ancient forests changed

When the dinosaurs went extinct, their absence changed the entire structure of forests, the team hypothesized.

“Large animals, such as dinosaurs, are known to alter their surrounding ecosystems. We think that if there were large dinosaurs roaming through the forest, they were likely knocking down trees, effectively maintaining forests more open than they are today,” Carvalho said.

After the dinosaurs disappeared, tropical forests became overgrown, and layers of trees created an understory and canopy. These dense forests made it difficult for plants to receive light, and they had to compete with one another for resources. And climbing plants had an advantage and used it to reach the canopy, the researchers said.

“In the fossil record, we start to see more plants that use vines to climb up trees, like grapes, around this time,” Herrera said.

Meanwhile, as a diverse set of birds and mammals began to populate Earth after the disappearance of the dinosaurs, they likely also helped spread grape seeds.

The resiliency of plants

Studying the seeds tells a story about how grapes spread, adapted and went extinct over thousands of years, showcasing their resiliency to survive in other parts of the world despite disappearing from Central and South America over time.

Several fossils are related to modern grapes and others are distant relatives or grapes native to the Western Hemisphere. For example, some of the fossil species can be traced to grapes that are only found in Asia and Africa today, but it’s unclear why the grapes went extinct in Central and South America, Herrera said.

“The new fossil species tell us a tumultuous and complex history,” he said. “We usually think of the diverse and modern rainforests as a ‘museum’ model, where all species accumulate over time. However, our study shows that extinction has been a major force in the evolution of the rainforests. Now we need to identify what caused those extinctions during the last 60 million years.”

Herrera wants to search for other examples of fossil plants, like sunflowers, orchids and pineapples, to see if they existed in ancient tropical forests.

Studying the origins and adaptations of plants in the past is helping scientists understand how they may fare during the climate crisis.

“I only hope that most living plant seeds adapt quickly to the current climate crisis. The fossil record of seeds is telling us that plants are resilient but can also completely disappear from an entire continent,” Herrera said.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com